Into The Andes: The High Road Through Ecuador

Pan-American Transmissions: Part 8

“Pan-American Transmissions” is a travel series from Special Contributor Diego Cupolo as he travels south from Nicaragua to Argentina. He has few plans, a $10-a-day budget and one flute-playing gypsy companion. Check back as new dispatches are posted from the road.

When Ania was a little girl in the Quebec countryside, her parents would lock her outside the house with her sister and tell the two to explore the forest until dinner time. No exceptions. On weekends, Ania’s entire family would go to the nearest mountain and run, not hike, to the summit. Once they reached the top, they would catch their breaths and then run back down. It was their way to exercise.

Through these rituals, Ania grew to be a first-class outdoorswoman. She had the heart of a mountain goat and the thirst of a camel. In her eyes, sitting still was a disease and she became anxious after spending so many months laying around on beautiful Caribbean, white sand beaches. Poor Ania — she needed a challenge. I, myself, was ready for a change of pace.

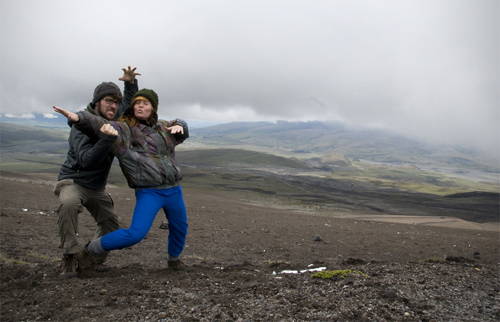

This was the mentality as our bus crossed into Ecuador, what many call the “Heart of the Andes.” Ania gazed out the window and smiled as she watched the surrounding mountains grow higher and larger, while at the same time, I sat in the aisle seat and watched the people around us grow shorter and rounder. We were in Andean country.

A new stage had begun in the journey. The mountain peaks passed by our bus, commanding our stares, calling our names and flute-heavy folk music echoed from ingeniously-wired speakers. We were excited. Thrilled. Few places in the world offer as much high-altitude magnificence as Ecuador and, by pure luck, we entered the country just as President Rafael Correa dropped entrance fees on all national parks. It was a hiker’s free-for-all — Ania’s dream come true.

We wasted no time. The flip-flops came off and the hiking boots were strapped on tight. We were determined to hike the Andes mountain range until our legs told us we could go no further. We started with the Imbabura Volcano and worked our way south to the Chimborazo Volcano, which is known to be the furthest point from the center of the earth (No, it’s not Everest — I’ll explain later). It took some time to get used to the high altitude and the low oxygen levels, but once we did, Ania and I shared some of the best hiking experience in our lives along the fabled cordilleras. The following are four accounts of four unconventional, low-budget, barely-planned climbing expeditions in Ecuador.

1) Imbabura Volcano – 15,190 ft (4,630 m)

The first stop was Caluqui, a small, indigenous village near Otavalo where the barbarous Imbabura Volcano watches over fertile mountain valleys. The year before, Ania had lived with a family in this mountainside community as part of a university program, so we paid her hosts a surprise visit. When the mother opened the door, she saw us and broke down into tears as the kids jumped around happily. The red-haired “Tia” had returned.

The family was so delighted to receive us that they killed a fresh chicken for dinner. We stayed at their place for about a week. Every morning Ania and I ate breakfast in the kitchen with our eyes gazing out the window at the Imbabura. The mighty volcano was practically at our doorstep and we watched the summit, waiting for the right conditions to start climbing.

Then, when the first clear day arrived, we set out early in the morning. The family told us there were no direct trails to the summit on our side of the volcano so we packed lightly — two apples, a few pieces of bread and one liter of water — thinking we’d go out for a short, easy hike. Nothing extreme.

We started walking. We passed through another small indigenous community and, soon enough, we began ascending the steep base of the volcano through patches of aqua-green eucalyptus trees. They smelled nice. Except for the occasional herd of grazing cows, Ania and I were completely alone with the land. We felt good. We were finally hiking the Andes.

We went up and up, crossed a gorge and continued up and up until we hit a thick wall of prickly berry bushes. “We’ll just go around,” I said. Neither of us felt like stopping so we walked along the volcano’s flank, looking for an opening in the bushes. We looked and looked, but never found one.

“Well, how far do you think the bushes go up?” Ania wondered. “They have to stop eventually. Let’s just try to make our way through.” I agreed and we ducked into the jungle of prickers and thorns. Each movement required planning. Every direction induced pain. The bushes were so thick we couldn’t stand up and we soon found ourselves crawling on our hands and knees through mud and moss and spikes of all sizes.

It went on like this for a half-an-hour before we realized the thorns weren’t ending anytime soon. Sure, it was miserable, but we figured it wouldn’t last much longer and kept pushing our way up the volcano through the thorns. An hour passed. Two hours passed. We were still in the berry bushes and we were getting tired. By this point we were well above two miles in altitude and it was getting hard to breathe. To make things more challenging, our hands were scratched to hell, our water had run out and we had consumed the little food we had in our bags.

“Okay,” I said. “I know it doesn’t sound right, but by now it’s probably easier to keep climbing up, get out of these bushes and try to find a trail back down. If we turn around here we’ll just spend another two hours in these damn thorns.”

We pushed and rolled. We became stuck; lacerated. Then, after three hours of pure torture, we popped out of the berry bushes into the yellow grasslands below the summit. It was a victorious moment.

Literally, “a” victorious moment. We dragged ourselves through the yellow grasses, without water, gasping for air, and couldn’t find a single trail. It was then that, reality gave us a firm slap in the face as we realized there was no way back down other than to go through the berry bushes . . . again.

Looking back on it, you could say passed a brief episode of pure crisis in that thick, yellow grass. The sun was low in the sky. It was starting to get cold. I didn’t know what to do and Ania started yelling violent obscenities in Quebecois French.

Lacking better options, we walked back down to the wall of bushes — tired, exasperated — took a moment to think things over and then dived head first into another three hours of thorns and pain. This time, at least, we used a pair of long sticks to aid the process.

Night had fallen by the time we came out the other end, scratched and angry (at ourselves mostly). We raced down the volcano’s foothills, found the nearest store, bought a big bottle of water and finished it within seconds. It was 9 p.m.when we got back to the family’s house, meaning 13 hours had passed since we left for our “short, easy hike.”

The mother laughed at our story and served us potato soup with quinoa. As I ate, I looked over my bleeding hands and I reflected on the miserable day. Maybe we were too eager to climb the Imbabura. Maybe we should’ve planned things out a little better — brought more food and water for instance. But one thing was certain: this was the wrong way to climb a volcano.

2) Cotopaxi Volcano – 19,347 ft. (5,897 m)

The thorn wounds were still fresh on our hands when we reached the Cotopaxi, Ecuador’s second-highest peak. Fortunately, this hike would play out much differently than the first. Cotopaxi is just south of Quito. On clear days its white, perfect cone is visible from the city center and it is beautiful, almost pornographic for high-altitude climbers.

Reaching this volcano’s summit is a serious matter. The Cotopaxi is so high it requires ice gear and professional guides (which at the time charged about $200 per person). Tour groups normally climb to a mountain refuge at 15,748 ft., eat, sleep in cots for a few hours, and then wake up at 12:30 a.m. to climb the rest of the way, reaching the top just as the sun rises. We were told tour operators climb at night because the snow is frozen hard and easier to grip with crampons, whereas during the day, the snow melts and is prone to avalanches.

Ania and I would have liked to reach the summit, but it was complicated and out of our budget. Instead, we took the easiest approach to climbing Cotopaxi and hitched a ride to a parking lot just above the Volcano’s snow line at 15,092 ft. high. From there, we joined other visitors who leave their cars and climb 656 ft. (200 meters) to the mountain refuge.

It sounds easy like an easy task, but it turns out to be a treacherous one-two -hour hike for the inexperienced. The path is not long or complicated, it’s simply the lack of oxygen at these elevations. The Cotopaxi put us in shame. A profound sense of worthlessness overcame my ego as I took three strides and gasped for air. It happened to all the visitors. About halfway up, a we saw a German girl vomiting her life because she hadn’t brought water. High Altitude Tip #1: drink excessive amounts of water.

When Ania and I got to the refuge celebrated by rolling in the snow. We sat down to eat cheese sandwiches and enjoyed the views. Cotopaxi is surrounded by gigantic, treeless, red, black and brown lava basins. Having so much open space present itself before us awakened strange, unknown senses. Our bodies where revitalized.

When we were done, Ania and I ran back down the volcano, passed the parking lot, and once again made our own path (this time keeping an eye on the nearest road). We surfed all the way down Cotopaxi’s side, sliding through mounds of black cinder until we reached a red canyon where an old lava flow had frozen in time.

The sun was shining, a group of wild horses galloped through the bare land and we took a promenade through the endless romance of it all. At the end of the day, we got back on the road and hitchhiked back to Quito. Easy.

The freedom we experienced on those bare lave plains made for one my favorite experiences of the voyage. No guides. No tour companies. Not even a single noise. It was just Ania, myself and the mountains. (Insert howling wind sound.)

3) Quilotoa Crater Lake – 12,841 ft. (3,914 m)

One of the Andes’s most serene landscapes was created by one of its most violent explosions. Two miles in width and about eight miles around, the Quilotoa caldera was formed after a VEI-6 eruption rattled the planet about 800 years ago. The blast was so powerful its gas plumes and muddy lava flows reached as far as the Pacific Ocean — just under 200 miles away.

As time passed, the dust settled and green, mineral-rich water filled the caldera to create an almost paranormal lagoon that has inspired many native legends about condors, falling feathers and lighting bolts. Today, visitors can easily access the lagoon by hiring a truck ($2 per person) from the nearby Quechuan village of Zumbahua. Some mountain lodge-style accommodations have recently been built near the crater, but they’re small, family-owned and charged between $7-$20 a night (meals included) at the time of our visit.

Regardless of new developments, the place remains beyond pristine, almost beyond words. Ania and I stood in shock the first time we looked over the ledge, down into the fluorescent waters of the lagoon. My eyebrows reached new heights on my forehead.

It may sound strange, but at first sight, the water in the Quilotoa was blurry, like something was floating above it. Inside it. It’s hard to describe. I stood there for a while, squinting my eyes, until I could make sense of what I was looking at — the waves, the clouds, the colors — and then, took a photo. But it was worthless. In an place so immense, an environment so ancient, what could a photo really capture?

I sat down and told Ania I wanted to stay by the crater side for at least a week. It seemed like a place that needed to be taken in slowly. Fifteen minutes later we got up and started walking the crater’s perimeter. The hike turned out to be one of the most scenic, least difficult expeditions we found in Ecuador. There was a photo in every direction I pointed my eyes.

Experts can hike the perimeter in about three hours, but casual hikers probably need four-five hours to do the loop. There are various ups and downs, making the hike challenging at times, but nothing too serious, and the altitude here doesn’t play as big a factor as it does on the volcanoes. It is also possible to hike down into the lagoon — a two-hour roundtrip.

Ania and I spent the day exploring the Quilotoa, taking breaks to take in the views, and chatting with the occasional sheep herder, though few spoke Spanish. It’s Quechua country in these regions and, until recently, the area was only populated by poor, ultra-isolated potato farmers. Tourism is still new to them.

By mid-afternoon, the clouds came in with a cold wind and swooped down into the caldera. Ania and I hurried back to our small lodge where alpaca blankets awaited us. The old housekeeper made chicken soup when we arrived and the long day ended as we huddled close to the fireplace in our little room.

It could’ve been the ideal honeymoon. All in all, the Quilotoa crater lake was our most enjoyable hiking experience in Ecuador. Simply writing this makes me wonder why we left . . .

4) Chimborazo Volcano – 20,702 ft. (6,310 m)

We saved Ecuador’s biggest volcano for the finale. While the Chimborazo is not as far above sea level as Mount Everest (29,029 ft.), it’s location near the equator makes it the furthest point from the center of the Earth. How’s this possible? Equatorial bulge. Centrifugal force caused by the Earth’s rotation basically stretches the planet’s crust outward into space. This pushes mountains near the equator further from the Earth’s core than mountains elsewhere on the planet.

Taking all this into account, Ania and I packed well for the expedition. Like the Cotopaxi, a tour company was needed to reach the summit and that was out of our budget, so we geared up as best we could (Ania bought an jacket from an old lady) and we headed out for our last great climb in Ecuador.

A cheap bus can be taken from the nearest city, Riobamba, to the volcano’s entrance, which starts you off at 15,912 ft. high. The trail up to the Chimborazo was a mix of black cinder, ash and volcanic rocks. We passed a few groups of llamas feeding on high altitude mosses, but they were shy and ran off whenever we tried to approach them.

We climbed and climbed. It got colder and colder. Sometimes it snowed and iced, but nothing could stop us this time. Ania and I had grown accustomed to the altitude by this point and we finally had the physical conditioning necessary to take on such a gargantuan mountain. Onwards! Upwards!

At some point we reach a mountain refuge that stood at 16,404 ft. above sea level and decided to duck indoors to warm up and eat lunch: apples, carrots, one loaf of bread and one big block of cheese. The high altitude deluxe.

We digested, took advantage of the fireplace, and headed out again to see how high we could go. The clouds came and went, reducing visibility to a few yards at times, but when it cleared up, we were able to catch glimpses of the summit — the furthest point from the center of the earth — and it didn’t look so far from us.

The block of cheese empowered us and we kept climbing until we reached a frozen lake that was about 17,200 ft. high. Soon after a thick fog engulfed us. It was a complete whiteout and the humidity brought a chill so crisp and brittle that we shivered down to our bone marrow.

But we enjoyed the moment. There wasn’t a single sound in the air, only the occasional chattering of teeth. The climb was an achievement. Neither I nor Ania had ever reached a place so high in the sky with our own two feet. We relished the moment and then ran back down the icy snow to warm up in the shelter one more time.

It snowed as we descended and the snow turned into rain by the time we reached the park entrance. There we found a group of construction workers that had just slaughtered a pig. They held up a jug of grain alcohol and gave us two big swigs each before inviting us to feast with them. It was the perfect ending to our journey. We ate greasy, fire-charred pieces of pork, took a few more swigs from the bottle, laughed, danced, and then thanked the group before hitchhiking back to Riobamba with a profound sense of satisfaction.

A Thirst for Climbing, Quenched

After our Imbabura mishap, Ania and I learned to better prepare ourselves for high-altitude hiking. Each time we climbed we were better fit for the conditions. It took weeks to acclimatize to the altitude, and each time we made it up the mountain we shared the Andean landscapes with fewer people than animals. How could we forget the experiences we had with the cows of Imbabura, the wild horses of Cotopaxi, the sheep herds of Quilotoa and the llamas of Chimborazo?

Maybe these animals had a special meaning or link with the mountains. Maybe they didn’t. The point is we were able to enjoy Ecuador’s premier hiking destinations on our own, freely, without tour groups, time schedules or any form of organization. Every hike was whatever we made of it and each expedition proved to be an extraordinary experience.

Most importantly, Ania, the Quebec mountain girl, got what she was looking for in Ecuador’s Andes. Her mountain goat heart was beating at ease. Thin air will do that to a person. The two of us thanked Correa for letting us into his parks for free and then strapped on our backpacks to head south to Peru.

By Diego Cupolo

Coming up next from Pan-American Transmissions: Lima: It’s Not As Gray As They Say. Read all of the other Pan-American Transmissions entries here.

About the Author

Diego Cupolo is a freelance photojournalist currently on the road to Tierra del Fuego. Most recently he served as Associate Editor for BushwickBK.com, an online newspaper in Brooklyn, and his work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Star-Ledger, The Australian Times, Discover Magazine and many other publications. View more of his work at DiegoCupolo.com.

Diego Cupolo is a freelance photojournalist currently on the road to Tierra del Fuego. Most recently he served as Associate Editor for BushwickBK.com, an online newspaper in Brooklyn, and his work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Star-Ledger, The Australian Times, Discover Magazine and many other publications. View more of his work at DiegoCupolo.com.