The post Top 10 Things to Do in Rio de Janeiro appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

From all holidays in the sun, Rio de Janeiro in Brazil might be the one with the most activities to partake in. With its vibrant nightlife, iconic attractions and one of the seven wonders of the world, the city, which was once the capital of Brazil, has a lot to offer travelers from all different tastes.

1) Museu do Amanhã (Museum of Tomorrow)

Designed by the neo-futuristic architect Santiago Calatrava, the applied science museum aims to create an open dialogue about the next 50 years. It takes in consideration all of man’s alteration of the world in its primary state while emphasizing ethical values and shining light on issues that need our urgent attention. Aside from the expositions available, the museum also hosts year-round classes, workshops and discussion panels.

2) Parque Lage

Designed by English landscaper John Tyndale back in 1840, this park is surrounded by the Atlantic Forest and is located at the bottom of Corcovado mountain. Easily accessible to the general public, the park is also known as a cultural hotspot by locals, as it houses a 14th-century house turned into a visual art school. A popular place to take pictures or have a romantic brunch is at Bistrô Plage, located in the mansion’s central patio by the pool.

3) Hang Gliding

For the sports aficionado, hang gliding will be an exciting and unforgettable activity filled with the best views from above.

As one of the most popular wind sports in the city, there are a lot of reliable companies which you can hire hang gliding equipment from. The ones situated in Pedra Bonita have the easiest access, being only 20 minutes from the Ipanema beach, and are known for having the best views. During this experience, remember to wear comfortable clothes, sunscreen and avoid taking big bags.

4) Escadaria Selarón (Selarón’s Steps)

Jorge Selarón, a Chilean-born ceramist, immigrated to Rio de Janeiro in the 1980s. Years later, in 1990, he decided to decorate the staircase near his house – which connects the Lapa neighborhood to the Santa Teresa neighborhood – as a tribute to Brazilians.

The staircase took 20 years to be completed and is made out of tiles and porcelain donated by Jorge’s friends and supporters. The landmark of 215 steps and the wall of both sides are decorated with painted tiles, now known as one of the most popular postcards of the city.

5) Maracanã Stadium

Officially called Jornalista Mário Filho Stadium, the soccer stadium is the most famous and largest in the country. Specially built for the 1950’s FIFA World Cup hosted in Brazil, the stadium got its nickname due to its location, the Maracanã neighborhood.

The historic stadium is known for many matches and moments of soccer history, but the most iconic one might be the 1,000th goal of soccer player Pele’s career. The stadium offers tours, but the best way to enjoy the place is by watching a soccer match, as soccer is one of Brazil’s biggest passions.

6) Lapa’s Nightlife

The Lapa neighborhood is known for being the center of Rio’s nightlife. When in Lapa, some of the must-do’s are watching a concert at Circo Voador, going for drinks at Bar da Boa, enjoying great Brazilian music and partying all night at the nightclub Lapa 40 Graus.

7) Ipanema Beach

The most famous and iconic beach of Rio de Janeiro (maybe the world), is responsible for inspiring the Brazilian song “Garota de Ipanema.”

The beach is the best place to take the perfect beach vacation pictures, especially at the Arpoador, the large rock that separates the Ipanema and Copacabana beach. At Station 9, many tourists and locals get together to watch the sunset, an experience which always ends with applauds from the public.

8) Irajá Gastrô

Opened in 2011, the restaurant with dishes by Chef Pedro de Artagão and drink menu by Julieta Carrizzo, offers the perfect pairing between food and drink. The restaurant only works with fresh and sustainable ingredients and has a cozy environment; the perfect place to go should you start to feel homesick or you’re simply looking for great food.

9) Sugarloaf Mountain

The Sugarloaf Mountain is made up of three hills: Sugarloaf, Urca and Babilônia. To get to the top, you can hike a trail or take the aerial cableway. The view along the hiking trails and on top of the mountain are both breathtaking, one of the best you will see during your lifetime. To get the most out of the experience, choose to go around 5 p.m. so you can watch the day transition from day to night.

10) Christ The Redeemer

Hands down the most popular tourist attraction to see in Rio, the Christ The Redeemer statue is an Art Deco masterpiece created by the French sculptor Paul Landowski. It was built by Brazilian engineer Heitor da Silva Costa and French engineer Albert Caquot, with the facial features fashioned by Romania’s Gheorghe Leonida. The sculpture was finished in 1931, eventually becoming one of the 7 Wonders of the World in 2006. You can enjoy a picturesque view from a few parts of town or get on the Corcorvado train to reach the top. If you plan on getting the train, make sure to purchase the tickets in advance as lines to purchase tickets can take hours.

/

Victoria Oliveira is a writer and translator from São Paulo, Brazil. Her first published article was for an international publication at the age of 14. She has since written for Matador Network, Youthgasm, The Culture-ist, and Elegant Magazine. She’s in love with desserts, learning new things, and exploring new places.

Victoria Oliveira is a writer and translator from São Paulo, Brazil. Her first published article was for an international publication at the age of 14. She has since written for Matador Network, Youthgasm, The Culture-ist, and Elegant Magazine. She’s in love with desserts, learning new things, and exploring new places.

The post Top 10 Things to Do in Rio de Janeiro appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

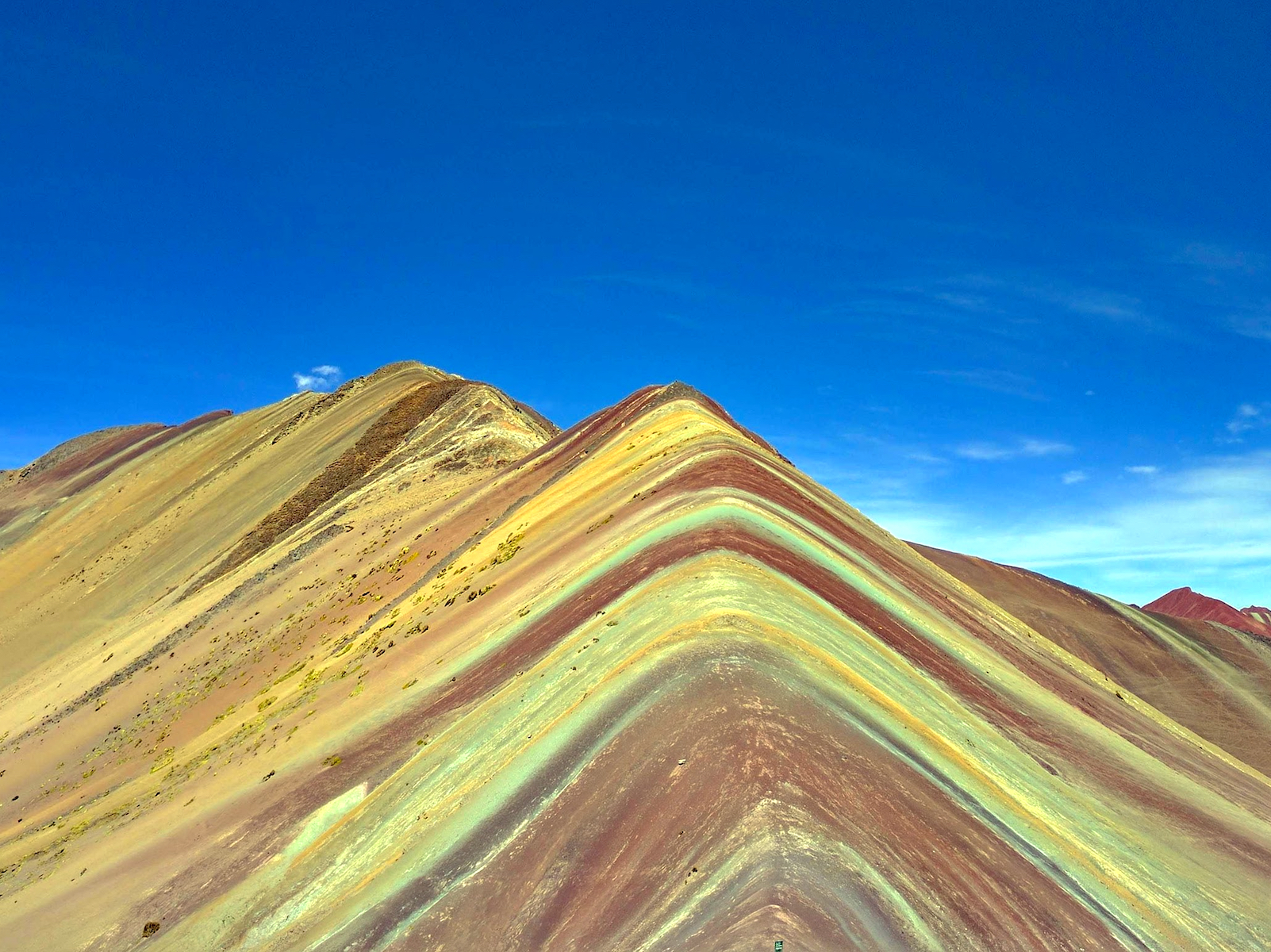

]]>The post Rainbow Mountain and the Search for Ausangate appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

Ausangate Mountain, an “Apu” (or holy mountain) in the Quechua culture, rises to 20,945 feet in the Peruvian Andes, hovering nearly 3,885 feet above Rainbow Mountain in the distance. For perspective, that’s 3,345 feet higher than the Mt. Everest base camp, 6,456 feet higher than the tallest mountain in the Continental United States, and nearly 15,665 feet higher than the “mile high city,” Denver, Colorado.

After a punishing two-hour trek straight up, sitting at the peak of Montana de Colores (Rainbow Mountain) next to a small stone wall built by the direct descendants of the Incan people, I popped open my first beer and spun in a dizzying swirl of colors. Ausangate rose in the distance like a giant, its glacier so massive that I mistook it for sky.

Standing below it, I now understood why the Quechua people called this mountain a diety.

I felt like a pilgrim, my body bruised, battered and broken, surviving the hike up Rainbow Mountain — like the Quechua do once a year — to stand at the face of the wise Ausangate, who is believed to hold the answer to any question.

Three and a Half Hours to the Trailhead

“Three hours,” the tour agent had said, with no mention of what was to come.

Jess and I sat on the other side of the desk, excited to see Rainbow Mountain but wary of a three-hour bus ride beginning at 3 A.M. the next morning. We had been traveling so much already, and we were not eager to feel like herded cattle again, jumping from bus to bus with strangers and having no idea if we were actually headed in the right direction.

She went on to tell us that lunch was included and they would pick us up from our hotel, but the extent of her English faded when our questions began. Still, we agreed, because the picture of Rainbow Mountain on the flyer looked too good to pass up.

“Three hours,” she said again as if to reassure us that we were doing the right thing.

There was no mention of one of the most dangerous roads in the world and our madman for a driver. There was no mention of marching through native people’s land without permission. And there was no mention of the breakfast of mystery meat and Tang that was supposed to fuel us for a strenuous day of bus rides and hiking.

If I would have known about the ill preparation and altitude sickness that would wait for us at the top of Rainbow Mountain, I don’t know if any photoshopped picture would have been enough to convince me to go.

Although, in the end, I’m glad that I did.

The Most Dangerous Road in Peru

The bus’s horn shook the gravel of the steep road. We had been speeding over cliffs, atop mountains and through deadly valleys carved by the rushing current of melted snow for an hour. The llama that often blocked our path gracefully charged out of the way of our madman driver as he threw us around turns with almost no regard for speed, sharing with us a sure image of our imminent bus crash.

I was silent, holding on to whatever control I had in silence, but others dealt with the terror of the road with laughter and jokes. We were all trying to pretend that our lives were not in danger, and we were all trying to hope that the ride would soon be over.

Bus after bus after bus moved through the villages in the valley like ants swarming a live beetle, honking their horns, telling the Quechuan people that they would not slow down — to get the hell out of the way. Sun-hardened faces peered up at us from fields filled with llama and sheep and crops still frozen by morning irrigation. We did not belong here, the faces said.

Children stared at us from fields or from the back of motorcycles that their elders drove, maybe wondering where we had come from. Of course, it wasn’t the first time that the indigenous people had seen a parade of buses move through their land like this. This road was built a couple of years before to shuttle tourists to the Quechuan scared site of Rainbow Mountain, and like everything else in Peru, sacred sites were big business: packaged, labeled and sold to the adventurous, first-world traveler, just like me. And judging from the number of buses that barreled through the villages, kicking up dust clouds that fell and covered the clay, hand-made structures of the Quechuan, business was booming.

“Three hours,” the tour agent had said the day before, but they were three hours that would turn into six. Two lanes that would turn into one. Hills that would turn into towering monstrosities of beauty. And ditches that would turn into chasms, showing us marveling views of our own possible death.

In the Shadow of Ausangate

“Everything conceals something else and there is no life without death . . .”

They were the words that I could not forget as I stumbled out of the van onto solid ground and stood at the trailhead before the Apu, the holy mountain.

Ausangate’s glacier scraped the sky and combined the line of earth and heaven. Its melting snow formed rivers that had cut the earth in half and created the life-filled valleys that the people we passed now called home.

It was no wonder to me that this holy mountain was a diety. It was no wonder to me that the people supposed that it could answer every question in life. It was no wonder to me that once a year the Quechua came from all over the region to search for answers and healing and life in this great Apu’s shadow.

The white of its peak was so untouched, so massive, that I double took. I had mistaken it for heaven.

Two Hours to the Top

The guide had said with broken English.

We had two hours to reach the top. Just two hours for a four-mile hike with a 5,000-foot elevation gain. Two hours of internal battle, broken spirits and escaped breath.

It’s right around the corner, I told myself.

But as I watched the mass of bodies move up the incline to where I thought the peak to lie, my heart dropped and my body shattered when the peak that I knew to be the top opened into a tundra wasteland.

To another peak.

To a distance that looked too far away to be real.

Each step brought us closer, but each step also brought us higher, toward thinning air.

I took my coat off, hoping that the fresh air and the lack of a heavy coat would help me breathe, but cold wind from the surrounding glaciers froze cold sweat to warm skin. My head was spinning from lack of oxygen and my fortitude was slowly leaking through the souls of my boots.

Caballito? (Pony?)

A Quechua man yelled at me.

Then another.

Then another.

They waited for my answer but ran past me when I didn’t speak. Some were wearing sandals. All were wearing short sleeves and did not seem to feel the cold or the lack of oxygen or the steep incline.

My eyes fell to my feet, hating the fact that I did not feel prepared. I was not used to the elevation, and I could no longer enjoy the beauty of the mountains with my head feeling like a balloon. With each step, my legs screamed and my lungs wanted for more . . .

Air, they said.

“Caballito?” another man asked.

“No, Gracias,” I said in my head, but the words would not come out. I could no longer afford to talk. The hike was becoming a lesson in suffocation.

“Caballo?” came a voice, then another, but I heard nothing. Only my own voice spoke quietly, telling me to put one foot in front of the other, to not look ahead. To just keep breathing. To take a break when you need it (which ended up being about every 20 steps).

This is only a small part of your life, I told myself, and I was right. The end was in sight.

When I finally looked up, when my eyes followed the line of bodies who were making the same journey as me, I knew that we were about to reach the top.

Steps rose before us, and we took them each with a painful gait, stopping every few to convince our legs to continue forward without air.

We were out of water. My legs felt broken. But there was light in the distance.

I saw a man selling beer at the top, and I felt a motivation to reach it as I’ve never felt before.

Rainbow Mountain

Rainbow Mountain sits roughly the same altitude as the Mt. Everest base camp. As I sat at the top of the mountain, cowering beside a small, stone wall that blocked the wind, my eyes beheld a sight that washed away the pain of the journey.

Red, yellow, green and blue combined on a ridge in stripes, each running into each other, each standing out from the other. The colors aligned in a sedimentary pattern that the wind had revealed over the ages, but it wasn’t just the colors that made the sight one to behold.

The Apu hung powerfully from the sky as if he had defined these colors. This place seemed to exist to grind a person to nothing. To make doubt of completion one’s singular thought. To crush one’s spirit so that they would be ready for the truth.

I sat at the top of the mountain with the woman I loved, gazing at the legend of an Apu who had the answer to any question I dared to ask. We had done the hardest thing that I had done in recent memory, and we had made it.

To ask a question seemed needless now.

/

Nathan Standridge is a traveling writer based out of Asheville, NC. He’s been seen trekking through San Franciscan streets at 4 A.M., drinking whiskey during a tornado in the Ozarks, and existing in silence among the temples of Chiang Mai. Follow his adventures through Thailand, Peru, and Italy at Foundinpursuit.com, or check out his book Change, available on Amazon.

Nathan Standridge is a traveling writer based out of Asheville, NC. He’s been seen trekking through San Franciscan streets at 4 A.M., drinking whiskey during a tornado in the Ozarks, and existing in silence among the temples of Chiang Mai. Follow his adventures through Thailand, Peru, and Italy at Foundinpursuit.com, or check out his book Change, available on Amazon.

The post Rainbow Mountain and the Search for Ausangate appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Maximón: Guatemala’s Chain-Smoking Savior appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

Floating mosaics of water lilies hug the sunken interiors of old buildings that line both sides of the dock. I sigh while staring at the jagged cement tops that barely pop above the surface. Water levels here have been rising steadily over the past 50 years.

“There used to be a huge park here . . .” the boat driver laments.

In many ways, Maximón — the vice-laden trickster deity of the Guatemalan highlands — is like these buildings. His foundations are visible yet submerged, planted below the surface yet reaching above. Like much in Latin America, he’s a mix of Spanish and Indigenous influences; a combination of San Simon from the Catholic tradition and earlier Mayan deities. To many of the Maya in Guatemala he’s known as Rilaj Maam.

Although his origins lie in the murky depths, legend states that Maximón was quite a Casanova back in the mythopoetic day. One day, while the men were off farming, he seduced all their wives. Upon returning, the angry farmers chopped off both his arms and legs. However, life hasn’t been that bad for the legless/armless deity.

Today you can find Maximón in many places throughout Guatemala, but Santiago Atitlán is the most famous. There you can see him draped in a garland of clip-on ties with a wide-brimmed hat dangling with silk as he’s offered gifts of Rubios cigarettes, bottles of Quetzalteca and money, in exchange for help in areas of business, marriage, crops, health, death and more.

On a cloudy afternoon during Guatemala’s rainy season, Sue, my travel companion, and I set out to find this notoriously dubious deity. There is something deeply appealing about a saint who can knock back a few shots of Quetzalteca — the harsh local hooch named after the national bird — and then dole out wisdom to those in need. He felt approachable.

We crouch onto the simple wooden benches of a water taxi, or lancha, at an empty dock in Panajachel and head off. It’s 30 minutes to Santiago Atitlán.

This city in the highlands is nestled between three volcanoes (Tolimán, Atitlán and San Pedro) and faces a lake Aldous Huxley famously called “the most beautiful in the world”: Lago de Atitlán. At 50,000 people, it’s the largest of the lakeside communities in Lake Atitlán.

Most of the local women wear purple-striped skirts and huipiles with floral designs and the older men are known for their white-striped pants. It’s an artistic hub popular for its Tz’utujil oil paintings — vibrant canvases that often depict a bird’s-eye view of rural scenes and landscapes.

Long before the arrival of the Spanish, the Tz’utujil Maya called this place Chuitinamit. It was their capital. To this day it still holds the largest population of Tz’utujil Maya in all of Guatemala. In 1547, in an effort to consolidate indigenous populations, Franciscan friars changed the name and established the town of Santiago.

At the height of the civil war in the 1980s, the Guatemalan army cracked down on the left-wing guerrilla presence here by killing and causing the “disappearance” of hundreds of villagers. A brutal massacre in 1990 saw 13 Tz’utujil Maya slaughtered by the army. Public outrage grew so strong that, for the first time in their history, the army was ousted by popular demand.

An elderly woman with cataract eyes and a handful of teeth walks barefoot down the street. On her head she balances a basket of bananas. We buy some, then ask for directions. She answers softly, in Tz’utujil, and sensing our baffled expressions, throws up a hand and points.

Down the road we go, past a gaggle of vendors and into a dead end. Left. Right. Hmmm . . .

“Maximón?” we ask and two kids hop into action — “come on” — and lead us a few yards down the road to a nondescript alleyway where a chicken slowly pecks away at his tin of food and a woman hangs up laundry to dry. We hand them a few quetzales and off they go running.

Inside the home, torrents of Copal incense are swirling back and forth, mimicking the laughter of the swaying drunks outside. The drunks are stumbling around their playground bar, gulping plastic bags filled with Quetzalteca that is stockpiled in bottles near the door.

Upon entering, a bored 12-year-old takes our entrance and “permission-to-take-photos” fee and heads off in the corner to ogle the scantily clad supermodels of the local periódico. We sit cross-legged, somewhat outside the ceremonial space, and try to be unobtrusive, a task that, many travelers come to learn, is nearly impossible.

We tease out our cameras and quietly snap a few photos as the ceremony begins.

A Man Asking for Help is sitting on a chair with a cowboy hat that’s drooping with floral cloth. His eyes meet ours for a brief moment, then turn back. Next to him on the bench is his family: a few small and restless children, a smiling wife and a stoic mother. Kneeling on three straw mats in front of 12 lit candles is an elderly man reciting prayers in Tz’utujil.

Patrons at the outdoor bar are cackling in the background and a man in a maroon-colored shirt who’s wearing dark sunglasses is talking on his cell phone as an unkempt dog lies nearby slowly licking his genitals. The Man Asking for Help is sitting inside this chaos, enclosed in the partial safety of family and prayers, and asking his silent questions. The elderly man is straightening out a wax candle stuck to the cement floor.

Ashtrays and candles separate us from Maximón, who is sitting immobilized between two helpers as he calmly puffs away at a Rubio cigarette. The gray ash falls to the floor as the smoke rises. The helpers are pouring him a shot of Quetzalteca and, soon after that slides down his wooden throat, they continue plying him with liquor, this time a glass of Gallo, the popular Guatemalan Beer.

These man are part of the cofradias, a respected few who are tasked with maintaining the proper veneration of Mayan and Catholic deities (observing their feast days, caring for them, etc . . .). This tradition was brought over from Europe to Guatemala by Franciscan missionaries in the 16th century. Their goal was to convert the locals, but the cofradias were reformatted to fit the personalities and schedules of important Mayan deities.

Just like the sudden influx of Europeans during the 16th century, the clamor and disruption of a large tour group is piling into the small room. As they begin complaining about the wafting smell of Copal and dust that envelopes the room, Sue and I know that it’s time to leave. We gather what we brought and slip out quietly, strolling down the narrow alleyway and onto the cobblestone streets.

As we wandered back towards the lancha, I reflected on this enigmatic deity. Maximón’s home had a unique feel to it that arose from the fact that it was not made to be unique. It wasn’t floating on some glorious mountaintop nor hidden in a far-off cave. It was calmly constructed inside a humble room next to a bar down a back alley.

Maximón was very much of this world and the ceremony was a jigsaw mix of the sacred and profane. Perhaps this was best for a saint who drinks, smokes and sleeps around. For someone who has made a mistake or two, this is a saint I could relate to: a saint who, at times, has been unsaintly.

Matt McGuire is a freelance writer and odd-jobs worker with a love for notebook paper, good books and the unwritten lines of the open road. His blog can be found at ThoughtWalks.com.

Matt McGuire is a freelance writer and odd-jobs worker with a love for notebook paper, good books and the unwritten lines of the open road. His blog can be found at ThoughtWalks.com.

The post Maximón: Guatemala’s Chain-Smoking Savior appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Go To Guate: Climb Acate appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

Examining my sleeping bag as I unravel it, I am relieved to see it is a proper sub-minus piece of kit. Not that I’m some sort of born-again Edmund Hillary-type, but you never know with these “adventure tour” outfits — some of them may as well send you off with a handkerchief and a glass egg cup for all the credibility of their equipment.

But nope, not this time. Be gone nature, we have Thinsulate!

I sink back into the legitimacy of down and allow my eyes to close.

BOOM.

Eyes snap open. Bolt upright, I scramble towards the entrance of the tent. Fumbling with the zip, the air fills with whoops and cheers of our fellow campers. Their glee echoes fragile and human above the rumble of earth belly beneath us.

Parting the canvas flaps — and there is no way not to make that sound gross — I gasp. Audibly. Like a cartoon character. Or, perhaps more aptly given the flap-parting, a porn-star.

What. A. Sight.

The moon is rising to the east of us. The sun is setting to the west. A sea of clouds drifts across the floor of Antigua valley, tinged orange, then pink, then violet as night draws in. Gradually stars emerge to pierce the purple blue of a deepening sky, winking coyly to the lightning that dances between distant thunderheads.

Bonfire crackling, colors melting: it’s the magic hour . . .

Then, once again: BOOM!

It’s a rare thing to observe a volcanic eruption at eye level, but this is Guatemala, and I have long since come to expect the fantastical. And indeed, here we are on the side of a volcano, watching another volcano erupt.

This shit just got Tolkien.

As the third highest volcano in the country, standing at 3,976 meters, Acatenango affords unrivaled views of its rather more rambunctious twin, Volcan De Fuego. It is, if you will forgive the metaphor, the relative safety of Middle-Earth to a sinister Mordor.

Having said that, I rescind my plea for forgiveness, for this is Gandalf territory indeed, and I defy you to contest this claim once having made the climb. You are even given a staff to assist you in the ascent for goodness sake. I mean, they call it a walking stick, but it’s so much more than that.

The next morning we rise at 4 a.m. to summit by sunrise. It’s high, its early and cold as balls. But it’s worth it.

The peak offers a terrific panorama of the coastal plains down to the Pacific in the South, and across the Guatemalan Highlands — including Lago de Atitlan — to the south. It is up there with one of the most beautiful sights any reasonable individual could ask to see in a lifetime. A smoking crater, 360 vista, proper breathtaking. Not that you’ll be able to take a picture of it if you are relying on your smart phone. Apples don’t like being chilly at altitude, apparently, so be aware that your camera will likely be hibernating when you need it most. Steve clearly wasn’t a man of the mountains. Or just really liked frozen fruit.

While it might seem that every man and his mother is offering trips up Acate out of Antigua, Guatemala, it really is a case of getting what you pay for. There are plenty of cheap-o alternatives, but having opted for Old Town Outfitters, I can recommend them highly. These guys know the mountains, they know their gear and they know how important it is to work in harmony with the local community.

Unlike the majority of the other tour companies operating this trip in the area, you will start your expedition from La Soledad, a small highland village about an hour’s drive outside of Antigua. Here you will pick up your local porters who, quite honestly, do most of the hard work for you, before setting off through farmlands to the trail, as well as start to get a sense of the role these volcanoes play in the daily lives of the people who live here.

So what are you waiting for? Go forth and channel that inner wizard! Oh, and this is a relatively strenuous hike, so dress accordingly, i.e., don’t be that douche wearing Converse.

P.S. Appropriate trekking attire may also include adorning yourself with a cloak and making the climb as Mr G. The Grey himself. In the event you subscribe to this option, kudos. Also, let’s get married.

***

[Photos 1 – 2 by David Leonowens; Photo 3 courtesy of Old Town Outfitters]

Old Town Outfitters, Adventureguatemala.com.

/

A journalist, human rights advocate and development professional, Hannah is currently located somewhere in the vicinity of Central America. As Lead Creative for an international freedom of speech project, she is passionately exploring ways to engage people and instigate positive change through innovative use of media, the arts and story. When she isn’t working, she’s probably scuba diving or being angry about Brexit. Life goal? Owning a house pig.

A journalist, human rights advocate and development professional, Hannah is currently located somewhere in the vicinity of Central America. As Lead Creative for an international freedom of speech project, she is passionately exploring ways to engage people and instigate positive change through innovative use of media, the arts and story. When she isn’t working, she’s probably scuba diving or being angry about Brexit. Life goal? Owning a house pig.

The post Go To Guate: Climb Acate appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post How To Pack A Wet Tent: A Trek Through Torres Del Paine, Chile appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

The mountain itself seemed to be hurling millions of tiny frozen pellets from every direction, some even rising up from the ground, all apparently aimed directly at our eyeballs. It was impossible to tell the depth of the snow, as it blasted across some rocks leaving them bare, and piled improbably high where larger rocks prevented its determined chase of the wind.

“You are lucky, this is the first snow of this year!” A park ranger gleefully shouted to us, bouncing by on legs that were much surer of the terrain than mine.

“Lucky?!” was all I managed to respond.

“Yes! We haven’t had snow since December, you’re the first to see it!”

At this point my boyfriend and I were halfway up Paso John Gardner, the highest point on the famous Paine Circuit, a backpacking route around Torres Del Paine National Park in Patagonia. The route forms a 75-mile loop around the sharp peaks and vertical towers of the mountains clustered in the center.

The park beckons hundreds of travelers to visit each day during high season (December through March), with more piling in each year. The insanely high popularity of the park necessitates strict rules for the hikers: no wandering off the single-marked trail, no camping outside designated tent sites, no walking on the trail at night. A trek through Torres Del Paine is not exactly a lonely wilderness quest, but nor is it approaching the sterile entertainment of a crowded Disney theme park, as some people claim.

The trek certainly lacks the creature comforts of a Disney Resort. The moment I woke up on the morning we planned to hike the pass, I regretted it. Before I opened my eyes, I heard weary drops of rain slapping the tent, the remnants of the assault of the previous night’s storm. I kept my eyes shut, trying to convince myself the sound was fading. “It will stop in a few minutes, I should stay in my sleeping bag for now,” I thought.

It didn’t stop.

The necessity of getting an early start on the pass, however, eventually dragged me out of the relative comfort of the nylon walls. It’s not that I didn’t want to be outside in the rain. I can deal with putting on my rain jacket and shivering a bit in the sharp morning air. It’s that I was poignantly aware of the excruciating task that sat in front of us, like an unavoidable pile of dog shit in the streets of Santiago: packing the wet tent.

We knew we would probably face this challenge at some point on our nine-day trek. Patagonian weather is notoriously moody, and the rangers even posted a sign at one campsite that reads: “Don’t ask us about the weather, it’s Patagonia!” In a single day, a hiker can seemingly experience all four seasons as the weather turns from sunny and warm to windy and rainy to snowy and cold.

During this particular morning, a drop in temperature caused fat, wet snowflakes to begin interspersing themselves among the tired raindrops by the time we finished breakfast. The only task left was to pack the tent. Mud had made its way into every crevice, and by the time we’d wrestled the clogged buckles apart and peeled off the sopping rainfly (that part of the tent meant to deflect rain) our hands were already stiff with cold. Each time the tent fabric brushed against my hands, it felt like sandpaper was being rubbed against the raw skin. My boyfriend and I did our best to stay patient as we folded the rainfly.

“Fold it in half. No, the other way.”

“I thought we wanted to fold it in on itself?”

“That’s what I’m doing!”

“Give me that corner. No, not like that.”

“It won’t fit like this though.”

After a tense minute, the rainfly was piled into a vaguely rectangular shape on the ground. Next were the stakes and poles, which were apparently cemented into their clips by a combination of mud and gravel. Once we finally coaxed them out and the poles were collapsed, it was time to roll up the tent with the rainfly.

The ground was too wet to kneel as I normally would, so I squatted like a frog and laboriously scooted forward as I rolled the fabric as best as I could with hands that refused to bend. Tears of pain and frustration blurred my vision as I lifted the roll of soaking nylon and my boyfriend shoved it, inch by inch, into the bag, forcing it to fit so we wouldn’t have to refold it. Finally, he cinched it shut and we were done. Despite the steep climb that lay ahead of us, we knew the hardest part of our day was over.

We pulled our packs on, tightened a strap here and a strap there, and started our hike. Energy came back to our spirits with the warmth of our blood flow as we walked up the trail. Soon after beginning our ascent of the pass, though, I developed an appreciation for the fierce Patagonian wind about which we’d been warned.

It’s not that the wind was relentless, but rather mischievous. One moment the mountain was completely still and a steady layer of snow fell from above, and within half a step a transparent force threatened to knock me to the ground (succeeding only once), while the falling pellets transformed into a swirling swarm of angry hornets. Ten or twenty steps later, it softened and remained quiet once again, coiling as a jack-in-the-box for its next powerful gust. My 40-pound backpack helped anchor me to the ground, but also acted as a giant sail pulling me backwards down the mountain with each push of the wind.

One step at a time, I defied both wind and gravity, shuffling up the mountainside at an embarrassingly slow pace. Half of my weight was entrusted entirely to my trekking poles as I leaned heavily into them, anticipating the next gust of wind. The rain and snow mix soon transformed completely into snow as we gained elevation. Partially frozen streams crisscrossed our route, and I prayed for no wind each time I precariously balanced myself atop the small stepping stones to avoid the freezing water.

It took four hours of careful trudging to reach the top. We stopped just a few times to admire the surroundings: the valley behind us that faded in and out of view with the clouds that passed over it, the needle-sharp ridges on each side that were too steep even for snow to stick, the thick glacier sitting just a few hundred feet to our right. All this was nothing compared to the view awaiting us on the other side.

Looking at Glacier Grey from the top of the pass felt like we were in the presence of eternity. The silent glacier rested in the valley beneath us, with ice stretching back through the valley and piling up the mountainsides, eventually melting into the flat white of the February clouds. It looked like a pencil drawing, a scene in black and white. Except for the blue. That weird blue that only exists in layers of snow and ice. Like a cross between turquoise and electric blue, but with a hint of indigo and a neon glow. The blue showed up where crevasses in the surface of the glacier allowed us a glimpse into its depths.

It was hard to believe that this seemingly infinite glacier was just one small bit of the massive Southern Patagonian Ice Field. At 104 square miles, Glacier Grey forms less than three percent of the 4,773-square-mile sheet of ice stretching across southern Chile and Argentina. The ice field represents the remnant of an even bigger ice sheet from the last glacial period, and now feeds dozens of glaciers across the continent. These glaciers are still carving the landscape of the region, scouring valleys and moving mountains with their incredible force.

The mountain didn’t allow us to enjoy the view of Glacier Grey for too long, forcing us to keep moving to escape the barrage of wind and snow. And so we descended, down the steep and muddy trail into the camp. Down beneath the snow, into clouds and rain and five more mornings of wrestling the tent into its bag at various levels of saturation, and into the more crowded section of the circuit trail, where we were soon to squelch ourselves into over-packed cooking shelters and swap trail stories with dozens of other trekkers.

And of course, we trekked down under the watchful gaze of the mountain, who stands sentry over this section of Patagonia as countless hikers scramble circles around her formidable base. I believe it is something about the juxtaposition of unique beauty and exhaustingly dark conditions that draws these hikers to submit to the shifting weather and experience the awe-inspiring bit of nature that is Torres Del Paine.

Laura works as a civil engineer to afford her true passions: backpacking, mountain biking, traveling, and writing. At the moment, she lives near Denver, Colorado, where she spends her free time playing in the Rocky Mountains and writing stories to share her adventures with others.

Laura works as a civil engineer to afford her true passions: backpacking, mountain biking, traveling, and writing. At the moment, she lives near Denver, Colorado, where she spends her free time playing in the Rocky Mountains and writing stories to share her adventures with others.

The post How To Pack A Wet Tent: A Trek Through Torres Del Paine, Chile appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Here’s What It Was Like Attending Colombia’s Craziest Festival appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

All the babies are crying, and an old lady starts yelling hysterically. As an enormous burst of turbulence turns my stomach sideways, I catch the eye of a man who looks like Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He gives me a gruff nod and half-smile, as if to assure me that the landing is always like this. I’m not convinced. Looking out the windows on both sides, men shout distances up to the cockpit, as if they were helping a neighbor parallel park. “10 meters!” “15 meters!” They are estimating the distance between the wingtips and the green peaks of the Andes. And the numbers they’re using are disturbingly small.

Though it wasn’t in the brochure, this is my introduction to the three-day, non-stop adrenaline rush that is the famous Carnaval de Negros y Blancos. Shaking a little bit, I step out into the one-plane airport of Pasto, Colombia, very near the Ecuadorian border. Now that they no longer herald a death stung by bits of fiery fuselage, the Andes are really quite beautiful. I even start to relax as I pass through the tiny terminal to the taxi stand. But there’s an ambush in place outside the airport. A group of teenagers cackle as they strafe the line of expectant family members and private taxi services, each armed with two cariocas, the basic-issue armament of the Carnaval participant. They are long, narrow aluminum cans containing something akin to shaving cream. I duck behind an old woman who takes the brunt of the fire. This will prove to be the only time I feel ashamed about using the elderly for protection. With their broad frames and slow movements, they really do provide the best cover.

After a harrowing hour-long taxi ride down a one-lane highway cutting through the mountains, where cars break through into oncoming traffic at blind turns with total impunity, I am finally in Pasto. The city itself, though small, is incredibly beautiful. Couched in the green mountains, under the watchful eye of an enormous dormant volcano, it has been a pilgrimage site in the area for hundreds of years. It’s full of historic churches, and this day of the carnival celebrates this element of the region’s culture. January 4 is the day commemorating the arrival of the Castañeda family, a pack of oddballs who passed through on their way to the Las Lajas sanctuary to the south. There’s a parade packed with men dressed as schoolgirls and women dressed as barbers prancing about as floats depicting confused children celebrate the general weirdness of people who pack up their families and walk hundreds of miles to look at a church.

It’s getting dark as I step out of my hotel to take place in the nocturnal revelries. I’m wearing my nice shoes and nice jeans, and don’t even think twice about it. I’ve read the Wiki on this thing. Today there’s a nice parade, tomorrow we’ll paint each other black, and the last day we’ll throw talc and foam and make a mess — the assault on the airport was an isolated incident. Tonight should be good clean fun.

Like all good festivals, the Blacks and Whites’ does not abide by its own rules.

I’m no more than ten steps outside my hotel when a family with two children eyes me head to toe in bemusement — we’re early in the carnival, and most tourists won’t arrive until the 6th to see the great parade, and even then they are not often American — before they each whip out the cariocas from behind their back and douse me from head to toe. While I’m desperately trying to clear the foam from my eyes, nose, ears and mouth, a window rolls down from a passing car and a talc-bomb catches me square in the chest. The doorman of my hotel laughs devilishly as I look around, trying to figure out what just happened.

One block further and a group of concerned-looking teenagers approaches me. Seeing how unprepared I am, they take pity and buy me my own carioca as well as a pair of sunglasses — the foam can sting your eyes, they explain to me. “No shit,” I tell them in my best Spanish. I follow them on their route, glad for the protection a few extra bodies can afford.

But their good nature is short-lived, or maybe entirely a ruse. They accompany me like bodyguards for a short time, leading me into the middle of one of Pasto’s two large squares dedicated to the carnival. As we push through throngs of people, I try to memorize the way back to my hotel, constantly wiping foam off of my sunglasses. Just when we reach the heart of the beast, the kids loudly call attention to my gringo presence. I will never see them again, as it takes nearly ten minutes to de-foam and de-talc myself, blindly stumbling through thousands of people to find shelter. This is the nature of warfare in Pasto.

The next day, the 5th, is the Blacks’ Day. I’ve planned a route for a morning stroll, hitting many of Pasto’s beautiful cathedrals and sanctuaries and also scouting out a good spot to view tomorrow’s Great Parade. I wear the same clothes, my battle gear, which will become impossibly ruined. With some paranoia I skulk about, peeking around corners, keeping an eye out for adolescents with cariocas. But they are still asleep, and the first to rise are the kind ones, the elderly and families with young children, who want to enjoy themselves before the mayhem starts.

I take a moment to breathe the cool, mountain air. A group of Colombianas, giggling, points me out. They turn around, conferring, then one of them slowly strides up to me. I stand stock-still; my conception of the carnival was more or less receiving undue attention from beautiful Colombian girls while parades and parties took place in my peripheral vision, and it seems to be coming true. She comes in for a kiss, cradling my face in her hands. There is a cold, oozing sensation, and as she pulls away before making contact I realize that her hands were overflowing with black paint. The 5th is officially in full swing as each of her friends more or less slap me with a handful of the same.

Later in the afternoon my cousin and photographer Jordan arrives in town. His wide-eyed expression and foam-covered bag communicate that he’s had a comparable experience to my own arriving into the city. We stroll around, paint and get painted, drink beers and talk with various groups, and enjoy warm Andean hospitality. Then, suddenly, the debauchery switches on. We come to realize that all the descriptions of the festival are true until about three in the afternoon, when the fabric of society dissolves under the chemical duress of 20 tons of shaving cream. Street vendors who have been hawking cold beers now change to aguardiente, the local anise-flavored liquor. The painting changes from delicate strokes by attractive women to more intrusive attacks. A boy no more than 12 years old sneaks up behind me and gets my whole nose and mouth with blue paint, which I will taste for a week. And then the cariocas come out.

Back at the hotel, we ask the security guard if it can get any crazier. He has worked outside the hotel every Carnaval for five years, which makes him a sage old veteran deserving of his epaulettes. He laughs at us. “Oh, that’s nothing, compared to tomorrow. You’ll want to buy a mask for your nose and mouth.”

And he’s absolutely right. The next day, the 6th, is the Whites’ Day and also the day of the grand parade, which starts early and goes for five or six hours under the hot sun. In Spanish it’s the Gran Desfile, which reads to American eyes like the Great Defiling, which is more or less what it is. Aguardiente hits the streets before the sun, and people who have grown impatient waiting for the parade to start get in massive carioca, flour and talc fights. Clouds of white massive enough to blot out the sun become a regular affair. It’s a study in the chain reaction — one sour look, one misfire of a carioca and suddenly a whole city block looks like the local Gillette factory had an accident. Tourists and the police patrolling the cordons are particular targets, though with so many people packed into such tight areas it is difficult to aim accurately.

Finally, the parade arrives. This is the reason why the festival is commemorated by UNESCO as a masterpiece of intangible cultural heritage, and it does not disappoint. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of colorful floats that have been the whole year in the making pass by, gradually increasing in size from enormous heads mounted on the shoulders of grunting, sweating men to converted buses and sixteen-wheelers. These are punctuated by musicians, dancers, circus performers, and scantily clad Colombianas.

There are nearly half a million people taking it all in, packed tighter than sardines, hanging from second-story balconies and sitting on towels wrapped over razor-wire walls. 50-pound paper mache political candidates box one another while KISS cover bands play local Andean music and women distribute smooches and candy. Marquez, who passed earlier this year, receives special attention with two or three large floats in his honor. The people are amazingly kind — people buy us beers wherever we go, Jordan and I finally get our Colombiana kisses, and we enjoy short-lived celebrity status. Mothers take pictures of us holding their babies. We each acquire about a dozen penpals. It’s paradise, until the sun starts to dip. Everybody knows what that means, including us. The rules that hold this fragile peace together will soon crumble. The apocalypse is coming.

Fearing the end of days, we spend our last night at a salsa bar three stories above the main plaza. Looking down, we can see nearly 50,000 people, which puts my first night of terror in perspective. Live concerts of a salsa-reggae mixed genre blare out at a hundred decibels. Generally, a salsa bar is a good place to hang out off the beaten track in Colombia. All the girls want a dance, and we embarrass ourselves thoroughly — “Remember, it’s just one-two. Don’t get fancy.” Occasionally, we lose sight of the crowd as a dusty white cloud permeates the square or a snowball of foam manages to make it up 30 feet to our position. But that’s the Carnaval. Cover your ears, your eyes, and your drinks.

And with that, the festival is over. We creep out on the 7th in our battle gear, expecting the same no-rules surprise attacks as the previous three days, but we look like fools. Everybody is dressed in business clothes and nicer casual-wear, nobody has sunglasses, and most of the destruction has already been washed away in an ever-swelling river of chalky talc and flour. An old woman leans up against a tree, bracing herself — she has an actual fire hose over her shoulder, and she is power-washing the façade of her fabric store. Her stream joins the rest of the white water, which will flow downhill into the ravines of the Andes, carrying away the last trace of the confluence of blacks and whites until next year.

Jordan A. (left) works as a web manager for Deseret Digital Media in Salt Lake City, Utah. He studied journalism and political science at Utah State University. Ski Krieger (right) is a physicist and writer based out of Providence, Rhode Island. When working or not, he’s steadily warbling as he prepares to compete in throat-singing competitions in Tuva.

Jordan A. (left) works as a web manager for Deseret Digital Media in Salt Lake City, Utah. He studied journalism and political science at Utah State University. Ski Krieger (right) is a physicist and writer based out of Providence, Rhode Island. When working or not, he’s steadily warbling as he prepares to compete in throat-singing competitions in Tuva.

The post Here’s What It Was Like Attending Colombia’s Craziest Festival appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Is There Anywhere Better To Shoot Video Than Brazil? appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>In honor of the World Cup wrapping up this weekend, I thought I’d feature this amazing compilation travel video from Brazil (as if the seemingly never-ending parade of enviable panoramic shots of Copacabana Beach and aerial views from Christ the Redeemer that have blanketed the airwaves recently haven’t already caused every sane person who hasn’t been to Brazil to scramble to their computer to check airfare prices to the country).

Made by videographer Tom Pinsard, this beautiful video was shot while Tom and his girlfriend were in Brazil for two weeks during the World Cup (they were wrapping up a six-month trip around Asia and South America).

Amazing footage as it is, unfortunately for us (and, well, Tom), one of his cameras was stolen while in Brazil, so he had to make do with the video he had already captured.

For those wondering, the video was shot using a combination of the Panasonic Lumix DMC-GH3, Sony Cyber-shot DSC-RX100 II and GoPro 3.

[Brazil by Tom Pinsard via Vimeo]

/

Matt Stabile is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of TheExpeditioner.com. You can read his writings, watch his travel videos, purchase the book he co-edited or contact him via email at any time at TheExpeditioner.com.

Matt Stabile is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of TheExpeditioner.com. You can read his writings, watch his travel videos, purchase the book he co-edited or contact him via email at any time at TheExpeditioner.com.

The post Is There Anywhere Better To Shoot Video Than Brazil? appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post My Discovery Of Eden In Semuc Champey, Guatemala appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

I’m riding in the back of an open truck that must have served to transport cattle at some point, but on this occasion, it is taking me from the town of Lanquín to the secluded community of Semuc Champey, in the heart of the Guatemalan jungle.

Riding with me is my girlfriend and about a dozen tall, heavy-set men. I exchange a few words with some of them and find out they are army guys, taking a vacation-break away from their training base several miles away. Right now though, they look mostly like tourists, goofing around and taking selfies as the jungle zooms by all around us.

The journey began in Antigua, a colonial city of pastel, multicolored houses, many of them former colonial estates, and a multitude of Baroque-styled cathedrals. At night, the cobblestone, quiet streets, dimly lit by the lampposts, transports me back to a pre-industrial era, a stark contrast to the Central Square area, where all the bars and cafes can be found, which give the city its vibrant nightlife and lively cultural scene.

Antigua is a key jumping-off point for moving deeper into Guatemala. From there it is easy to get a 6-hour-long bus ride to the town of Lanquin, some six miles away from Semuc Champey. While the climate is temperate in the higher altitudes of Antigua, the moment you get off the bus in Lanquin, you know you’re right in the tropical jungle.

Lanquín is the last stop where I can get what most Westerners consider everyday commodities, like all-day electricity, cell reception or internet connection. The community of Semuc is found one cattle-truck ride away, on the banks of the Cahabon river. This is a protected natural area and local custom holds great respect for the environment. The locals are for the most parts descendants of Q’eqchi’ Mayans, and many of them still speak — sometimes exclusively — the local dialect, Q’eqchi.

In Q’eqchi, Semuc Champey means, “Where the river hides beneath the earth,” which references a nearby location at the bottom of a steep valley called El Sumidero, where the Cahabón River flows underground, then comes back out at a source called El Manantial. This forms a natural stone bridge over 1,000 feet long, above which are a series of natural, turquoise-colored pools of pure spring water, streaming downriver in a steady flow.

I arrive at one of the few available accommodations nearby, a small eco-hotel called El Recreo, which runs on solar panels and generators, and is mostly built of rock, palm and adobe. A couple of girls in colorful, hand-woven dresses, who hardly speak a word of Spanish, come to greet us and pitch us some of their homemade produce, cocoa candies.

Looking back on it, this was actually one of the most memorable local delicacies I came across. The candies were homemade bars of pure cocoa paste, pressed by hand, mixed with spices, including cinnamon, chili and cardamom. I still sometimes get a deep, nostalgic craving for those spiced cocoa bars that those little girls made by hand and sold for a couple of quetzales to the tourists that came by.

There are abundant cocoa trees all around, and I learn from the hotelkeeper that you can crack a cocoa nut open and find a juicy, tender fruit inside, wrapped around the seeds and strongly resembling a human brain in appearance. The housekeeper tells me that in local lore, this is actually because cocoa fruit is said to be good for the brain. The fruit is sour, juicy and tender, incredibly tasty, and while most of us are familiar with cocoa nut, I realize most people have never even tried cocoa fruit, let alone even known it exists.

There is little to do during the day in Semuc Champey, but what a setting to do nothing at all. I’m inside the jungle, next to the river, reading, swimming and walking around town, which consists mostly of farms interconnected by trails through the jungle.

Throughout the days, I end up realizing everything goes at a different rhythm than I’m used to here. My girlfriend and I end up befriending the little girls who sell cocoa candies. They teach us a few words of Q’eqchi’, like Saq’ e’ (Sun) and ha (water). My girlfriend has an easier time learning the language than me. I suspect that after a month talking to these girls, she would be able to speak fluent Q’eqchi. The girls give us a tour around town, including a trip across the natural stone bridge to the entrance of a nearby reserve. On the way, we see the army men swimming in those turquoise pools. They wave at us from the distance, looking like kids fooling around in the water.

I am told there is a cave network nearby called Kam-Ba, where the river flows underground. I am led a couple of miles down to the entrance of a cave. There, we are handed candles and guided in through the complete darkness. The water was sometimes waist-high as I followed the dim light of the guide. Walking in front of me into the cavern, the open space seemed to stretched onward until it could reach the bowels of the earth — a sort-of entrance to a Mayan underworld. Bad idea to lose your light in here, which is exactly what our guide tells us to do after a while. Inside, in the darkness of the cave, all you can hear is the dripping from the stalactites and the occasional flapping of bat wings.

On our way back, I am given an inflatable tire and am allowed to drift on a slow, scenic ride down the river, which ends with a little swim back to the riverbank facing the hotel. I am exhausted. That night we get to build a bonfire on the riverbed with some of the other guests, who are, for the most part, international, barefoot backpackers on a budget, and we stay out stargazing through the treetops, listening to the sounds of the jungle.

There is, in particular, a strident whistling that I imagined could only come from some local bird. Actually, I am told that this sound is emitted by a small insect called a chicharra. There is a constant, chirping, hissing, coo-cooing, all around us. All of these sounds intermingle, creating a rhythmic beat that never ceases. You tend to think that the nighttime in the jungle is silent, but it is actually surprisingly noisy.

It was tough to leave Semuc. After just a few days there I had gotten used to the rhythm, to the constant, high-pitched chirping of the chicharras, and to sitting on the riverbank, watching the river flow.

The girls wave us good bye. The off-duty army members are nowhere to be seen, probably floating downriver on an inner-tube, in the beer-induced stupor that only a leave of absence can bring on. I get my last load of cocoa candy, and the girls wave us off as the cattle truck drives uphill. As we leave town, the humidity lifts instantly, and I feel like we’re leaving a small patch of Eden behind.

/

Mateo Garcia is a freelance author, journalist and travel writer. You can check out his blog at TrippyFiction.blogspot.com.

Mateo Garcia is a freelance author, journalist and travel writer. You can check out his blog at TrippyFiction.blogspot.com.

The post My Discovery Of Eden In Semuc Champey, Guatemala appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Greetings From Brazil [Travel Video] appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>Heading to the World Cup in Brazil next month? Yeah, me neither, although any and all invitations that include a spot on a couch in someone’s rented house and/or an extra seat on their jet to get down there are welcomed and highly encouraged here at The Expeditioner HQ.

To get you in the mood for all the envious social media photos and TV footage you’ll be seeing during the games, check out this fun video from the Delinquent Valley crew, entitled “Greetings from Brazil,” featuring some great, intentionally retro-ized footage from the country.

/

Matt Stabile is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of TheExpeditioner.com. You can read his writings, watch his travel videos, purchase the book he co-edited or contact him via email at any time at TheExpeditioner.com.

Matt Stabile is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of TheExpeditioner.com. You can read his writings, watch his travel videos, purchase the book he co-edited or contact him via email at any time at TheExpeditioner.com.

The post Greetings From Brazil [Travel Video] appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Ducks, Drugs And Dance Meditation: My Failed Stay At A Nicaraguan Permaculture Farm appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

The man walked blindfolded between our outstretched fingers as we caressed him with leaves and feathers. Other hands reached out to caress or hold him.

“You are loved,” someone whispered.

“I love you,” echoed another.

He ended his walk in the arms of the oldest man and woman on the farm. They cradled him as would a mother and father, rocking him gently. This unusual birthday ritual captured in a nutshell my stay at a remote permaculture farm on Nicaragua’s Isla de Ometepe — a loving, community-centered experience that managed to both charm and profoundly weird me out.

I was fresh off a week-long spiritual retreat in Lake Atitlan, Guatemala. I’d left refreshed, relaxed and ready to put aside my Toronto-forged cynicism. I’d traveled down by chicken bus and ferry to this farm caught in the dip between two volcanoes, one fire and one water.

My first impression of the property seemed to promise further connection to the earth, self, and community — all things which I’d begun to foster in Guatemala. The farm was run on solar power and had a big garden filled with local crops. Its bounty fed the farm’s full-time staff, volunteers and visitors. Additional supplies such as grains were almost all local. There was a rustic open kitchen, a meditation hut with views over the palm-filled valley, a library and hangout center, and a pool with sweeping views of the fire volcano and the lake far below.

An elfin blonde beauty with freckled blue eyes and nicotine=stained teeth showed me around. I waxed poetic about the farm to her. It seemed like the hippie colony I had wished for and yet had always misanthropically avoided.

It all started to unravel that night. I was sitting on a rock bench in the open kitchen and enjoying the rich scent of yucca cooking in coconut curry when a tall and lanky guy with Napoleon Dynamite glasses sat next to me. He skipped the small talk and instead began to stroke my back. I instantly freaked out. One of the interesting things about getting out of your comfort zone is realizing how small that zone really is. It only took one (supposedly) innocent touch to put me out of it. That was only the beginning.

At least I was faring better than the duck that was on its way to the lower field teepee. A retreat was on and the participants were to meet the duck before he was made into soup. After this an intense night of drumming, chanting and imbibing of some beverage that would induce lucidity was scheduled to begin. Even the smallest amount of marijuana pulled me into an abyss of fear, so this all sounded incredibly sinister. I’m sure the duck would have agreed.

The next day I decided that I had to make inroads with the other folks staying at the farm. Trying to be a joiner, I trekked 30 minutes downhill to the closest restaurant with a few other residents. I chatted up a bronzed Canadian who was head cook in the kitchen. He confessed that he grew pot in British Columbia half the year and traveled the rest. He was at the farm to try to clean up his act and face his demons. He was a former party boy with a golden face and a haughty manner and he seemed deeply uncomfortable with himself and most other people. I resigned myself to the fact that he wasn’t going to be my new best friend.

I turned to a didgeridoo-playing Dutch guy instead. I quickly found out that he had the unnerving habit of staring right through you while asking overly personal questions. He posed them as if he was riding on some sparkling wave of honesty when in fact he was in the no-beeswax zone. I had heard him playing his instrument down the hill, the low eerie sounds wafting out of the tall grasses.

At least the gooey oven-cooked pizzas and I got along. I sat on a park bench and watched lithe women glide by in brightly patterned harem pants, belly tops and dreads. We eventually walked back to the farm together along the snaking path, the stars blotting out the sky above with their dazzling scatter. The total darkness obscured my steps. I stumbled over rocks and roots and ducked underneath almost invisible strands of barbed wire.

Monday morning rolled around and with it came the return of yoga and meditation classes. I was relieved for a bit of structure and decided to throw myself into getting in touch with the inner me or God or whatever happened to be there.

At 5 a.m. I groggily stumbled towards the tree-top Jungle House. I expected the rest of the crew, but to my surprise, only the owner, Jane (a serious woman with long dreadlocks and a sinewy yoga body) and her German boyfriend were there. I was the only student.

They instructed me to let me body move, vibrate or emit sounds as it liked while a feral-sounding electronic music played at top volume in the background. I never felt more rigid in my life, except for when my boyfriend had tried to teach me salsa dancing. I stood there with my eyes closed while tapping my foot and praying for the whole thing to be over.

Yoga wasn’t much better. Most classes were taught by volunteers who had recently completed their teacher training. The worst class by far was led by my back patting friend. He decided that leading us through traditional yoga poses was too square and turned the whole session into an impromptu laughter yoga class.

Back-patter started making up moves and laughing his crazy hyena laugh. The pot dealer/head cook proceeded to crack up which precipitated a chain of frantic laughter while we all sprawled in ridiculous poses. It was kind of great, except that I really wanted to stretch and I hate laughing. The latter point is mostly not true.

The whole experience was kind of harmless in and of itself. The lame classes, the angry hippies, the strange rituals and random cuddliness were somewhat balanced by the intense and savage beauty of Ometepe, the relaxed pace of life and the delicious vegetarian food that was heavily laced with succulent coconut, fresh cacao and curry.

What tipped it all into the red was José, the farm’s carpenter. Native to the island, he was short, deeply tanned and had a mouth full of silver fillings. I’d quickly taken to him. He thought the farm’s hippies were ridiculous and since my cynical defense mechanism had kicked back in he proved to be a much-needed friend. I gave him English lessons, ate dinner with him and answered his barrage of questions. I knew that his intentions were no purer than those in the hearts of the hippies around me but I figured I could keep him at bay.

Still one night he invited me to sleep with him in his loft space and everything came crashing in. I realized that I was stuck on the farm in the middle of nowhere with no ally, no sense of purpose and definitely no inner peace. I was deeply uncomfortable. I begged Jane to let me out of my 10-day commitment.

She let me go though not before looking deeply into my eyes and saying, “You think people don’t notice Bronwyn but I see your pain.”

I stumbled back down the rugged path towards the village, tears stinging in my eyes and my pack weighing heavily on my back. I’d said a quick goodbye to José before I left.

“You will forget me,” he’d said before I hurried off.

He was right, I would forget him. What I wouldn’t forget was how I’d had a terrible experience in a supposed spiritual paradise. Some of it was due to bad management and the rest came from my inner resistance and inflexible boundaries. My last encounter with Jane showed me that there was a vein of giving that I had refused to mine.

I realized that Guatemala had showed me my best self while Nicaragua had shown me my worst. I was as surprised by my own reactions as the people and places I’d encountered and I needed to process that experience. And avoid hippie birthday parties at all costs.

[Isla de Ometepe by Eric Molina/Flickr; Volcán Concepción by m.a.r.c./Flickr]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bronwyn Kienapple is a freelance writer and Canadian who’s currently lost in Southeast Asia. Her writing has appeared in such publications as Torontoist, The Grid and Toronto Standard. She recently contributed to the literary cookbook Eat It: Sex, Food & Women’s Writing.

Bronwyn Kienapple is a freelance writer and Canadian who’s currently lost in Southeast Asia. Her writing has appeared in such publications as Torontoist, The Grid and Toronto Standard. She recently contributed to the literary cookbook Eat It: Sex, Food & Women’s Writing.

The post Ducks, Drugs And Dance Meditation: My Failed Stay At A Nicaraguan Permaculture Farm appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Here’s What You Can Expect During A Food Tour Of Veracruz appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

The air outside is thick, but the smoke in Santana’s bar is thicker. Even if I were a non-smoker it would be worth it just to sit in the bar’s tiny, air-conditioned seating area and watch the old men slowly drink themselves into an affectionate stupor at three in the afternoon.

This is the first stop on my locals-only, rambling tour of Veracruz, Mexico, and we’re starting with beer. This crescent-shaped state straddles the eastern portion of Mexico along the Gulf of Mexico and is famous for its history of pirates, Carnaval and the uniquely Son Jarocho style of music with its indigenous, Spanish and African musical influences — all indicative of its unique location.

Santana’s has an upside down emergency exit route sign placed gingerly between cracks in the wall. I imagine if there were a real emergency that no one would hurry to the door — no one here seems to be in a hurry to do anything. An old jukebox in the corner sits silent and a list on the wall advertises a bottle of tequila for 500 pesos (about $40). Thank God the beers are only 16 pesos.

My photographer friend, Joyce García, is a Santana’s regular. She was born in the port and when she returns to visit family she makes the bar her own personal office because of its free internet and cheap beers. “This place gets crazy,” she says as an entire salsa band walks through the door and starts to play. “Just wait a few hours.”

After a couple of songs and a couple more beers we leave Santana’s aquamarine walls and head down Zaragoza street to Bar Titos. Posters of half-naked women on the walls give the bar its racy element but the atmosphere is otherwise tame, with a few couples swinging to norteña music and kids wandering in and out, looking to sell candy or watch the soccer game for a few minutes. No air-conditioning here, just slow, lazy fans pushing around the salty Veracruz air.

When we get to Noche Buena bar on Arista street, I immediately fall in love with its swinging wooden doors. Every old cantina should have a wild west feel to it. Tonight, a Wednesday without a live band, the mood is relaxed and customers sit in clusters, sipping tequilas and sucking on limes sprinkled with salt. On the T.V. behind the bar, 1950’s Mexican movies play and a cat named Alfonsa rubs up against me begging for attention.

We take a break from drinking to sample the fare at Joyce’s favorite tacos de guisado stand, Los Gueros, in front of Sanborns restaurant off the main plaza. She orders a sweet tamale de elote and I eat a pork taco in spicy green tomatillo sauce and one of egg mixed with mild chile pasilla. We share an horchata — the classic rice milk drink with hints of cinnamon.

We set out from the stand on a night ramble through the historic center’s plazas. I am remembering one that I stumbled upon on my last visit here when I was a mere tourist without my local tour guide. There was a Cuban son band playing that night, and old and young couples were swaying to the music on the street. Men double my age and half my height even asked me to dance.

I find out it’s called la Plaza de la Campana for the large bell that looms over the plaza’s cement stage. You can find music there regularly. This night a band plays boleros — Mexican love songs — to a crowd seated around tables. The plaza is ringed by seafood restaurants and tiny torta shops and spectators appear to be settling in to watch until dawn.

La plaza de la Lagunilla is also lovely, with a square of park benches filled with kissing, whispering lovers and a statue of Benny Moré, the famous Cuban composer who was adopted by the Veracruz people as a native son.

La Pachanga is the last stop on the night’s pub crawl. It sits across from Veracruz’s famous portales and is the city’s late-night locals hangout. On the weekend, cumbia and salsa bands entertain the slightly lit crowds of dancers, revelers, lovers and those looking for love. After a few tequilas everyone is up and dancing, even though tonight it’s only music over the speakers and the morning is slowly washing in like the Veracruz tide.

Breakfast for Veracruzanos means picadas (flat thick tortillas with a smear of beans, salsa and cheese), gordas (puffed dough that resembles tiny elephant ears made either savory or sweet) and tacos de cochinita pibil from David’s taco stand on Gómez Farías street. David’s cochinita is not like cochinita in Mexico City, where the pork is swimming in a spicy garlic and achiote sauce. This version is a mild and fragrant cochinita broth ladled on top of tightly rolled pulled-pork tacos. The stand is only open from 10 to 4 everyday. Thank God or I would probably have eaten every meal there during my visit.

Seafood is ubiquitous in Veracruz. The city’s coastal location has not only made it an important shipping port, but also a vital source of the mariscos that jarochos — Veracruz locals — are crazy about. We’re too late for the fish market that is 10 minutes outside of town. Its stalls start to shutter their doors by 3 p.m. most days and the real action there is in the morning. But we do find El Torbellino, a local seafood restaurant without all the cheesy nautical decorations and annoying waiters hassling you at the door.

We eat a plate of snail ceviche — thick, tender snail meat “cooked” by lime juice and mixed with a sprinkling of fresh tomatoes and cilantro — and sample a shrimp cocktail that is less sweet than most I have had in Mexico. Both taste amazing, especially with a cold beer, although we agree that the texture of the snail takes some getting used to.

The following day we wander away from the city’s heat and take the bus to Coatepec for a final culinary escapade. Joyce assures me that this mountain town has the best coffee in Mexico and after visiting I tend to agree. Avelino’s cafe, downtown Coatepec in front of the San Jerónimo church, is a shrine to the roasted bean, and owner Avelino Hernández sits with us for over an hour talking about his upcoming book, Las Frutas Encendidas, and coffee’s spiritual qualities.

We also visit the Resobado bakery, which looks like an old woodworking shop and smells like heaven. Along its spartan walls are wood-fired pastries and breads, and the place permeates with the smell of yeast and campfire. We buy cookies with piñocillo (a type of Mexican brown sugar), wheat yeast rolls and conchas (sweet bread).

I want to be able to say that Coatepec is truly the best place for visiting coffee-lovers and so as a security measure we stop at Cafetal Apan for a final cup of coffee. I’m not let down. In fact more than down, the caffeine gives me a buzz I won’t lose for a couple of hours until we’re finally sitting in Las Tradiciones restaurant in the Costa Verde neighborhood downtown Veracruz chowing down on steaming hot ground beef and potato empanadas and drinking cold beers in the pouring rain.

I’m in a bit of a panic at this point that I haven’t yet tried the Naval hotdogs or been to Emily’s Antojitos on Zapata street that I heard is incredible. I also want to make my own seafood feast in Joyce’s kitchen from what I can find at the fish market. But time is running out. I decide incredible empanadas are not a bad final feast.

By Lydia Carey

[Photos by Joyce García]

Locations

Santana’s Bar

Zaragoza

(In front of Los Portales)

Veracruz

Bar Titos

Zaragoza 208

Veracruz

Rest-Bar Noche Buena

Mariano Arista 803

Veracruz

(229) 932-5122

La Pachanga

Mario Molina 100

Veracruz

Tacos de David

Corner of Gómez Farías and Esteban Morales

(In front of Notiver)

Veracruz

Mercado la plaza del mar (Veracruz Fish Market)

Corner of J.M. García and Fidel Velásque

Veracruz

El Torbellino

Corner of Esteban Morales and Zaragoza

Veracruz

Avelino’s Cafe

Mansión de Los Azulejos

Aldama 4

Coatepec

(228) 816-3401

Resobado Bakery

Constitución 3

(228) 817-8888

Coatepec

Cafetal Apan

Constitución 48

Coatepec

Las Tradiciones Restaurante

Mar Mediterráneo 338

Veracruz

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lydia Carey is a full-time writer and translator living in Mexico City who loves to eat. Her work has been published in Mexico’s English-language newspaper The News and The New World Review. She can be contacted at carey.lydia8[at]gmail.com.

Lydia Carey is a full-time writer and translator living in Mexico City who loves to eat. Her work has been published in Mexico’s English-language newspaper The News and The New World Review. She can be contacted at carey.lydia8[at]gmail.com.

The post Here’s What You Can Expect During A Food Tour Of Veracruz appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>The post Turning The Car Around: One Road To Expatriatism appeared first on The Expeditioner Travel Site.

]]>

Stories can be told from limitless angles of perspective. So let’s begin this tale from the viewpoint of a Salvadorian family living in a small, rural village. It is a sunshiny day in a one-goat town a few hours drive and world away from the busy capital — a place far removed from the beaches and bars where gringos tend to roam. The day begins no different as previous days, weeks and months. A young couple with a four-year-old son and eight-year-old daughter tend their one-room store across the street from their home. One of their more valuable possessions, a female goat, is tied in front of their store.