This Is Russia

Nizhniy Novgorod, Russia — mid-January or early February. It’s dark and the temperature is somewhere in the subzero category. Seems late for 4:00 p.m. My eyelashes clump, heavy with frost, and my glasses are permanently iced over. The snow seems to be falling at a rate of several inches per minute. Square wooden shanties sit on the hill to my left like squalid gingerbread houses, lost in heaps of grayish icing. On my right, a few Soviet-era apartment buildings cast warped shadows across our path of drifting snow.

“Seriously you guys, where are we?” I ask, slightly exasperated but still good-natured. Riley responds with the learned nonchalance of someone who has traveled through Europe alone with little regard for personal safety, despite having acquired genital lice in a public bathroom somewhere between Switzerland and Spain.

“I dunno dude, but this is like, the sketchiest place ever. Did you see that unmarked van drive by? And check this junkyard out, what the . . . ?”

“This is Russia,” Monica offers, dryly, and we pause our marching to laugh at our new favorite catchphrase. It sums up everything so obviously, so perfectly.

“But why Russia?” my mother had asked. “Why can’t you go somewhere else? I don’t like the idea of you living there, being a girl and everything. Russia is so dangerous.”

“I don’t know, I just — I really wanna go, Mom.”

I couldn’t articulate the appeal of existentialism and the idea of the Russian soul to my mother. She’d probably assume I was a godless, communist wreck. Plus, I’ve never been very aware of why I want what I want, I simply stubbornly insist on having it. In retrospect, I was hoping to find the Russia of Russian literature. I’d been reading Tolstoy, Pasternak and Bulgakov, and I was longing for a people who embraced suffering. Or maybe I was just an angst-ridden teenager, trying to find myself.

The first time I read Crime and Punishment, I was hooked. I was in junior high, and it was summertime. I stayed inside for a few days and experienced all of the ecstatic despair that Raskolnikov felt. I was overcome by Sonia’s forgiveness and Raskolnikov’s redemption. I remember running outside in a book-crazed stupor after finishing the novel, proclaiming my thirst for meaning to the north Idaho twilight, to the weedy pasture outside my house and the tangle of trees just beyond. I might have dramatically kneeled and kissed the earth, praying to the God of my parents and the God of my childhood, for all the forgiveness a sheltered 13-year-old girl could possibly need.

At 21, the book was initially just as energizing. I smoked skinny cigarettes and downed teapot after teapot as I understood more of the uniquely Russian details from my perch above Ploshad Gorkovo in Nizhniy Novgorod. But about halfway through the book, I no longer cared about the Russia of 19-Century Russian literature and only half-heartedly finished reading my copy of Dostoyevsky’s classic. “Sonia is pathetic,” I sighed to my host mom’s empty apartment.

Raskolnikov goes from being a crazy, relatable mess to being so Christian — so predictable and tame. The answer to his existential struggle could not be this. It could not be this faith I’d shaken freshman year. The book still had literary merit, but I had no connection to it anymore. I didn’t understand Raskolnikov’s triumph in Siberia, and I no longer felt his redemption. I was jaded. Dostoyevsky used to be Russia to me, but as I looked down at the crowd of fur coats and hats at the bus stop seven stories below me, I realized I didn’t know who Russia was or whether I liked her all that much anymore.

One night, shortly after my arrival in Nizhniy, I met a snarky, outgoing Russian boy named Vladimir who spoke some English. He knew I was American the instant he saw my short hair and goofy grin. He seemed both intrigued and repulsed by this, and insisted on being called Lenin to make me uncomfortable. He didn’t realize that I was not your typical Cold War kid; comparing himself to Lenin was no more threatening than encountering the real Lenin (who I’d strolled past a couple times by then, as he lay embalmed and blackening in the mausoleum).

“Ah em Lenin.” He grinned. “Zee eveel comuneest. Ah play sport of hockey an’ dreenk all zhe vodka an’ beat mah womin becus ah am from Rossia.”

He laughed but his eyes were hard and bitter. National identity is a funny thing.

Nizhniy Novgorod is situated in European Russia’s heartland at the confluence of the Volga and Oka Rivers, about 300 miles or a day’s train ride east of Moscow and two and a half days south of St. Petersburg. The city was founded a couple centuries before Columbus discovered the New World, and it was a thriving metropolis and center for merchants. Russian people used to refer to it as the “Pocketbook of Russia.” Nizhniy is still important in the region, but not the economic powerhouse it used to be. The nicest areas of downtown are just a few blocks away from rows of decrepit wooden houses with broken-out windows; not unlike pictures I’d seen of shantytowns or Hoovervilles in my history textbooks.

During the Soviet period, the name Nizhniy Novgorod, which basically means “new city,” was replaced by the name “Gorky,” because of the famous — and overly didactic — Soviet author who spent his childhood there, Maxim Gorky. Gorky was not his real name or patronymic; it is the Russian word for “bitter,” which, as anyone who has read his work can tell you, accurately describes the life of this man who grew up in pre-Bolshevik Revolution squalor.

Nizhniy has a population of over a million people and is the fifth largest city in Russia, yet no one west of Kiev seems to have heard of it. I read the Wikipedia entry before I left the U.S., but gleaned most of this information later on a tour from Russian students who were eager to explain the history of their home to me. Between 1917 and 1991, Nizhniy was closed to all foreigners. In four months, my group of 15 American students met three other Americans — two missionaries and one student.

*

It’s late April or early May. Monica, Riley and I are lost again. We notice a pile of books next to someone’s garbage can on the side of the street. Monica hurries over to inspect them.

“They’re probably smutty paperbacks,” I remark. “Don’t get too excited.”

We scoop some up at random and hurry along because we need to find our way back before it gets late. As we walk, Riley sounds out the more difficult Russian titles so we can decide which ones are worth keeping.

“Wait, is this one about pineapples? Okay, here’s an old looking one: Doctor something. Zhi-vah-go — dude! I found Doctor Zhivago!”

Doctor Zhivago had to be sneaked out of the USSR to be published because much of the material in the book was deemed anti-Soviet. This particular copy was a hardback from 1957 — the very first year it was printed by a French publishing company and smuggled back into the country. It wasn’t legally published in Russia until 1988, almost 30 years after Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Now, in capitalist Russia, this classic work of dissident literature sits next to plastic trashcans and empty beer bottles, collecting dust and curious foreigners.

I saw Russian soil for the first time after I’d been living in Nizhniy for over three months. The Motherland — when I finally glimpsed her bare earth — was filthy. Garbage littered every muddy, slushy street and square of the city, and I had to dodge puddle water every time a bus sloshed past.

When the last of the snow melted, everything that wasn’t brick turned from mud to dust in what seemed like hours. It was alarming to see the starkness of a horizon not obscured by heaps of snow. I went for long walks by the Volga River, passing 15th and 16th Century cathedrals as well as strip clubs. Old Believer Orthodox Christians in their long, black smocks and beards walk past scantily clad nightclubbers without a backward glance.

Groups of four or five people — sometimes students, sometimes middle-aged adults — would stand just off the street, sharing a bottle of vodka. When everything was still frozen, they’d place the bottle in a bank of snow to keep it cool, then pull it out and pass it around, laughing and smoking. When it was warmer, they switched to liters of beer. The first few times I encountered these groups I was shocked, but by the second month I was joining them on their liquid picnics. Once, we crawled underneath a table in a pile of trashed furniture where we could hide from the wind and snow and talked haltingly about God between shots. Vodka is cheaper than milk in Russia, and better at warming your insides.

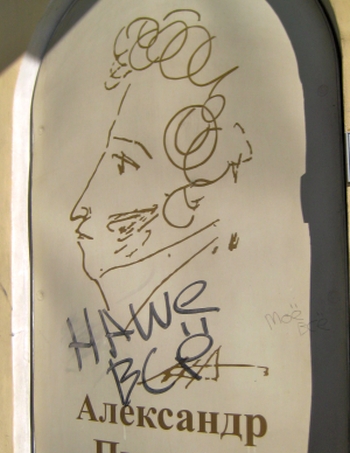

Outside of a restaurant in St. Petersburg, I saw graffiti scrawled on a portrait of Alexander Pushkin. It read, “Our everything.” I realized then that I needed to know the Russia of today for who she really sometimes was: the Russia of disillusionment; the Russia of corruption, alcoholism, depression and early death. The Russia who threw Pasternak out like trash while her delinquents scrawled literary references instead of expletives on the walls of their cities. The Russia whose suffering is becoming a new literature.

While going to Nizhniy Novgorod State University, I learned Russia had the highest literacy rate in the world during the height of the Soviet Union. My Russian friends could quote Pushkin, Chekhov, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky without hesitation. How many American students could quote Whitman, Melville, Fitzgerald or Emerson without being called pretentious assholes?

I taught American history to university students so that they could listen to a native speaker and practice English vocabulary in their field of study. There was one student, Sasha, who always sat in the front in pressed suits. He treated me like an ignorant foreigner most of the time, muttering what I assumed to be insults under his breath. The rest of the students generally found this quite funny, avoiding my eye contact as they giggled. On the last day of class, he approached me, blushing.

“Maybey not all Amereekans are bahd.” He shrugged, looking at the floorboards.

I wanted to hug him but I think my face remained mostly emotionless as I responded.

“Spasibo, Sasha.” Thank you.

By Crystal Stuvland

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Crystal is just another twenty-something kid from the woods of north Idaho who recently fled the country to live and work in Ecuador. When she’s not running from one adventure to the next, she tries to understand and write about the life of a wayfarer. Read about her misadventures and musings at Simplyontherun.Blogspot.com.

Crystal is just another twenty-something kid from the woods of north Idaho who recently fled the country to live and work in Ecuador. When she’s not running from one adventure to the next, she tries to understand and write about the life of a wayfarer. Read about her misadventures and musings at Simplyontherun.Blogspot.com.