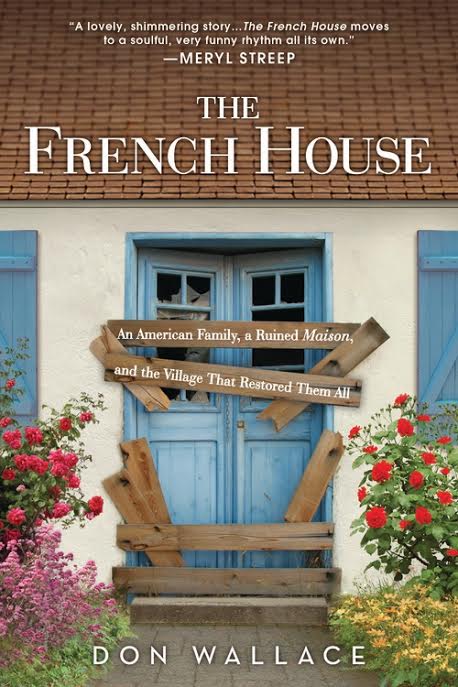

Book Excerpt: ‘The French House’ By Don Wallace

The following is an excerpt from The French House: An American Family, a Ruined Maison, and the Village That Restored Them All, by Don Wallace.

Chapter one

Far Breton

It’s another day in Kerbordardoué.

Up at eight, before the others. The sun doesn’t set until nine thirty or ten during summer at this latitude, so it feels early. Treasuring the quiet, moving like a French Country Ninja, I put on the water, light the gas stove, quietly clean off the wineglasses, dessert plates, and empty bottles from last night. I ease open the window facing the dining table. A giant flowering bush pushes inside. It has to be pushed back outside every evening, like a last inebriated guest. I inhale herb–scented air, listen to the buzz of the bees. The square is empty, the village silent, the sky pink from sun diffused through a cottony marine haze.

With a faint crunch of gravel underfoot, Suzanne strolls into view, hands clasped behind her back, trailed by a kitten. She’s in her usual blue apron over her usual blue–black shirtdress, the same outfit she’s worn every day for the last ten years, and probably every adult day of her life. The kitten dances with her heels and boxes the hem of her dress.

Suzanne moseys over to the well in the wall. Terraced sides of uneven stones form a veritable Hanging Garden of Babylon with the clippings she has inserted into the moist crevices. Her fingers fuss, tamping and fixing. She plucks a few live shoots to tuck into her apron pockets and transplant elsewhere. Then, hands clasped behind her back, she continues her promenade up the lane, past our door, eyes sweeping the flowers and shrubs along our thin verge of garden, most of which she’s planted and tended when we’re away, back in the States. If she were to raise her eyes, she’d see me. But like most older Bellilois, she tries not to look into windows or open doorways. Or at least if she does, to not get caught.

A hiss from water spitting from the pot breaks the spell, sends me back to the stove. She probably knows I’m watching, anyway.

Tap–tap–tap. Work has started somewhere. Peering out through the lace curtains on our door’s window, hand–knitted by Suzanne, I spot a close–cropped head rising above the tile roofline of the tall A–framed cowshed across the square. Rolling a dozen nails between his lips, Loup slides slates into place and tap–tap–taps. Another slate down, nine thousand to go.

A well–muscled guy with a large tattoo of his German shepherd on his bicep, Loup is single–handedly rehabbing the long, narrow building. He’s restored the exterior walls to simple drystone glory, a seventeenth–century skill he had to teach himself. He’s ripped out the cow stalls and laid a floor of antique salvage oak, then an upper story where once swallows nested and shat. I’ve seen the future of the cowshed and it’s gorgeous: a building that sat ignored and decaying for forty years will soon be mistaken for an elegant village relic. Parisian women will set their snares for Loup, only to find themselves flustered and outsmarted by his first love, work. Meanwhile, one more blackened tooth in Kerbordardoué’s crooked smile will be restored.

Clad in chic powder blue running togs, the blond wife of the Unforgiving Couple steps out into the square and does a quick set of bends and stretches. Fifteen years ago, the couple bought the empty lot across from us, a field of weeds spanned by rusted arches of iron that formerly supported the roof of a barn. Mindy and I took the loss of our view—-a blue line of sea—-stoically. One day the arches would be attractive hazards for our son and the village children, we thought.

But before we could meet the couple, they submitted plans for a three–story McMansion to the Mairie de Sauzon, or mayor’s office. Once enough people had taken a look and gagged, Gwened the Archer led a charm offensive. The couple blew her off. Gwened took our protest to the Mairie de Sauzon, who dismissed her as a mere second–home owner, even though her grandfather was from Belle Île and she had been coming here her whole life.

When she informed him about the regulations on the books and how they forbade a third story, he patronized her. That did it. Gwened went door to door with a petition, the first, some said, in island history. About half of the second–home owners signed it, but not us—-Gwened felt having un étranger Américain would backfire. The Bellilois elected not to sign: such is the strength of feeling here about imposing one’s opinions on others. When Gwened returned to the Mairie, he shrugged. Madame, we have never been presented with a petition and this is not the time to start.

That left the fate of that lot to our village’s widowed matriarch, owner of the surrounding fields. No way the stern and reserved Madame Morgane would sign anything so forward as a petition, but she agreed to go to the post office, which was next door to the Mairie de Sauzon, who happened to be in, with his door wide open to the street. Naturally he greeted her. A conversation took place. The subject almost didn’t come up. Then he scoffed at all this foolishness. She replied that the new house would be “too tall.”

Too tall? The Mairie frowned. The first plan was rejected. A second came in with two stories—-but enormous glass walls. This was actually easier for the Mairie to reject. There are laws against that sort of thing. Belle Île enjoys national heritage status, which specifically covers home construction and renovation.

The couple responded by building a house without any windows facing the square, which was fine with us once some ivy grew up the blank white wall. In fifteen years, I can’t remember them once waving hello. It’s really too bad.

Oh, well. They don’t come from here. They don’t even come from somebody, as the political machine hacks say in Chicago.

At least we come from “somebody” — and gratefully. Gwened. She lured us here—-invited us to Belle Île when we were reeling around Europe fifteen years ago, our dream of living and writing in Paris having come undone. Mindy had been her student long before, in the campus abroad program where Gwened taught. Gwened had offered us her house and ended up changing our life.

The wife runs off, hippity–hop, classic le jogging style. Spooning out black mounds of cheap supermarket coffee, as good and aromatic as any of the expensive beans I noisily grind in our kitchen back in New York, I pour the boiling water into a cone filter wobbling atop a brown pot hand–thrown by our Scandinavian potter neighbor. Suddenly a voice echoes in my head: My very own randy Dane up the lane…

It’s my sister’s joke, from her visit a year ago, and a bit unfair—-though the potter certainly did trail Anne around his atelier in the fields. What a view to a seduction he had: fat yellow heads of buckwheat bending to the breeze, then a dark dense green windbreak of cypresses, and after that, the wide, glittering blue–steel sea. The Atlantic. Pure horizon.

His tanned fingers kneading Anne’s arm, finding more muscle than expected, he cried out in English: “But you are strong!” Excited, as if imagining her churning butter on his Viking homestead, walking behind the plow, a baby crooked in each arm.

“Merci,” she said, mustering all her French. With a flutter of her eyelashes she pulled away. “Unfortunately, we really must be going.”

“Just think,” Anne sighed that day, after we rode away on our rickety bikes, the potter waving forlornly to our backs. “If I ran away with him, we could live in adjoining villages and pay each other visits at teatime.”

“That would be nice,” said Mindy.

“We could have Earl Grey in cups made by my very own randy Dane up the lane.”

“Anne!” Mindy shrieked. Et voilà! The quip attached itself to the pot like a superfluous handle.

Mindy always says Anne is the sister she never had. They laugh together, joke together, surf Huntington Beach’s Chair 16 together. But we don’t see enough of her. Since at different hours of the day Anne is a mother, a wife, a stepmother, a daughter, a schoolteacher, a golf teacher, and a writer, I’m sure nobody sees enough of her. Living on opposite coasts doesn’t help, which is our fault for moving to New York City.

As I sat there, watching the coffee drip into the brown potter’s cups, I missed my sister and considered how hard that trip must have been for her. Getting Anne over here is a project of ours. She’s chafed at living in our hometown all her life. Once or twice she almost left, but for some reason at the city limits, life always pulled a U–turn.

The first time she was about to make her escape from Long Beach, on a yearlong surf safari down to Mexico and South America with her boyfriend, the car broke down on the freeway on–ramp. Our parents came down hard on the guy, and they broke up. Before I even heard about any of this, she was engaged to the son of our father’s business partner, who proposed, I think, on the golf course. Anne had two young kids before the marriage went bad. She might have gone south to make a new start, but in the same week she was diagnosed with stage IV throat cancer. Divorced and healed up after miracle surgery and radiation, she found a man. He wouldn’t commit.

Then the current one came along, a carpenter who surfed and read The New Yorker. Ideal, right? She married him. But already there were strains. Anne’s teenaged daughter was acting out big–time. And, underlying everything, a deeper tension rattled my sister’s confidence. She’d confided to me that she’d glimpsed the pattern of her life and vowed that, no matter what, she’d bust out one day, if only to Seal Beach, just across the county line.

As I was helping Anne to engineer her escape to Belle Île, I fed her air routes and plans for her whole family to come. Circumstances combined to whittle it down to just her and her son. When she hesitated, I supplied rationales for a vacation from the tempestuous daughter, the teaching job, the old dog, cat, and plants—-oh, yes, and from her husband’s three kids on alternate weekends. She definitely needed a break, I argued. And successfully.

But what I didn’t realize was how selfish that was. All these people loved her and had legitimate claims on her. I was beginning to see I really wanted her to validate Belle Île for me. I wanted to see Belle Île through her eyes. And to watch her fall in love with it. After so much family criticism over our coming here, of all places, rather than closer to home in California, I wanted to see her pick up on the way the island was like all those idyllic Pacific coves and beaches we knew when we were children, before the bulldozers and housing tracts. Like those places, but better. I wanted to give Anne this, and then surely she’d do as we’d done—-make every effort to return every year.

Belle Île was already Mindy’s and my alternative base from home, established over the protests of our families. Now, like every breakaway republic, we were recruiting, and because Anne was the shining light, the radiant one, among the Wallaces, I’d introduced a conflict of loyalties, forcing her to choose between us and the rest of the family. She saw it. I didn’t, not yet.

Once I got my wish and she was here, of course Anne would be Anne. On her third day here last summer, she watched me prepare for a picnic with the kids at the Hidden Grotto of Swimming Lizards. “I want to play that thirteen–hole golf course,” she said. “Sarah Bernhardt’s golf course. The first course started by a woman. I can sell a story about that to Golf for Women and pay most of my expenses here.” She tossed her head back and laughed, as if feeling the fingers of the wind coursing through her hair. “You can write one, too, Donny. And you, Mindy. We can make so much money and expense dinners at the Hôtel du Fart.”

*

“Du Phare,” corrected Mindy, laughing at Anne’s wicked mispronunciation of our island’s most picturesque restaurant. “Pronounced far, meaning lighthouse.”

“Wait! Then what’s that dessert we had at Hôtel du Pharrrrt? ”

“Far Breton.”

“Lighthouse cake?”

“Noooo…”

Anne was having such a good time mangling the language that it actually made me jealous. Normally that was my gig. At dinner at the Hôtel du Phare she’d feigned confusion at every menu choice, fruites des mer becoming “fruit of a female horse” instead of a seafood plate and so forth, ending with the rubbery egg and prune concoction called “Far Breton.”

“Wait—-how can phare be a lighthouse and far a cake?”

“One word is French, the other Breton,” I explained.

“Well, I think that for you, Far Breton means ‘sweet distance,’” she replied curtly.

Snark from Anne was a surprise. “Meaning?”

“You didn’t just go for the Far Breton,” she said mock accusatively. “You went for the Far, Far Breton.”

“Look, I like Long Beach.” Our hometown.

“Funny way to show it, going ten thousand miles away.”

“Only five. Look at Mindy. Hawaii’s even farther.”

“Far, far, far.” Anne shook her head. Message delivered: we were too far away. Though I still didn’t know from whom, I could guess: Mom.

But, being Anne, she immediately deflected the point of the barb toward herself. “And I still can’t get out of Long Beach.”

This actually caused a pang of remorse. I felt she’d read my mind, that she thought that I thought she’d missed out on life. Stuck in the old hometown, repeating herself. I couldn’t reply.

*

My morning reverie comes to an end when our eleven–year–old, Rory, and David, Anne’s son, tumble downstairs and briefly struggle over which of the deep wicker chairs to sit in. There’s no difference, except for a matter of placement. The far end of the table is the prize. Mumbling good morning, they attack their waiting cups of hot cocoa and Krispy Rolls “Suedoise”—-a kind of Swedish hardtack.

But all is repetition here, too, I should’ve protested to Anne. If only she had come this year, too—-but, instead, she sent her giant teenager to eat us out of house and home. Fortunately, we love Devo, a six–foot–four high schooler. Even better, he came bearing an envelope of cash with “Feed Me” written on it.

Mindy has been upstairs for a while, writing in her journal. Now she comes for her coffee and Krispy Rolls. We have only a few scrapes of blackberry jam left in the jar but plenty of butter. Only in France do we put butter on bread. There’s no point in trying it in the States; I’ve tried, and it doesn’t taste anything like the incomparable beauty of French beurre.

Crunching and sipping, the boys lean over the chessboard and begin setting up the pieces.

“No!” shouts Mindy. “No chess until you make a surf check.” Mindy can’t plan her day unless she knows whether there are waves.

“Hmm,” says Devo. “No surf check until checkmate.” He moves his pawn.

“No lunch unless you make surf check. Chop–chop! Now!” Mindy claps her hands loudly. Yesterday the boys started playing a game and didn’t leave the house until early afternoon. This plays hell with our schedule, such as it is. The threat of no lunch usually works. When it doesn’t, and we abandon the boys to their own devices, there is a definite danger that the house won’t be there when we return, due to the combination of Devo’s appetite and the stove, knob-less after several explosions.

“Your move.”

“I’ll make you an omelet if you check surf now,” Mindy pleads.

“Hmm. What kind of omelet?”

“Chorizo and tomatoes and Gruyere.”

“Okay.” Devo looks at Rory. Then, with a crash, both shove their chairs back and race for the door. There’s a struggle at the handle that Rory loses, being a foot shorter and seventy pounds lighter than his older cousin. But he’s faster and arrives first at the bikes leaning against Gwened’s barn. One bike’s chain slips; the other doesn’t. Another struggle begins.

“Peace at last,” I murmur. “More coffee?”

“Sure. And an omelet.”

“Hey!”

“I want to write while it’s quiet. Everything is so noisy here.”

This is a slight exaggeration, considering that in New York City, garbage trucks groan and drunks sing and clubbers fight and hookers hook and then swear at each other under our windows from midnight to dawn. But everything is relative. I understand that.

Through the window I see the boys whiz past down the rutted lane. I grit my teeth and wait for the crash at the bottom turn. Nothing happens. Good.

A surf check means we have at least twenty–four minutes of peace—-nine for the boys to pedal madly up the road, take the shortcut across the fields, descend the treacherous dirt lane to the paved road, pedal madly up to the turn to the village of Kerhuel, pedal madly through Kerhuel dodging free–range chickens and sleeping dogs and one–eyed cats, then pedal madly to the cliff and the overlook. You can’t do an honest surf check from where the road ends, so they’ll have to run to the cliff edge, which takes three minutes. We’ve charged them with providing specific answers to our questions, so that means at least two minutes watching, though we’d prefer ten. The return trip is a bit faster, involving less uphill.

“Maybe we have time?” Mindy nods at the stairs and arches an eyebrow.

“Well…” I check my watch. “Twenty minutes.” We look at each other, counting off the seconds. Once the boys made it back in nineteen. We trade glances: too risky. Not relaxing.

“Okay,” Mindy says. “Make sure they rinse their feet at the door.”

Back to the stove I go. Chop garlic and onion, slice rounds of hard Spanish chorizo, the Don Moroni brand that I smuggle back to the United States each year. Diced green peppers and tomatoes also go into the skillet. While they’re cooking, I crack six eggs into a bowl, add some milk, and stir.

Spatula in hand, I drift over to the front door, open it, and stand barefoot on the concrete stoop, worn by weather and summer feet. Pushing through the billowing hydrangeas that mask her patio and front entrance from the square, Gwened emerges holding a paper high in the air.

“Oh, Don! I have a letter from Daniel!” She’s wearing a simple floral frock with a scooped neck that shows off her deep tan, cleavage, and a gold orb on a chain that dangles there. On her feet are the rope espadrilles that Gene Kelly and Bridget Bardot made famous. You can always rely on Gwened for a fabulous entrance.

She switches into French for my daily grammar workout. We talk about Daniel, her son who lives in the United States. He’s found a job doing art therapy at a hospital. Life is good. His wife is trying her hand at writing articles for a newspaper. Will I correspond with her, pass along advice and encouragement? Of course.

Recalling my duties at the stove, I dash in to slide the sautéed vegetables onto a plate and pour the beaten eggs into the skillet. Gwened waves and moves on down the lane, letter in hand. I suspect she will stop at Suzanne’s plain stone house. Then, if Le Vic is out sunning himself while his sons and wife garden, she’ll pause at his white picket fence for a chat, then sweep up the road to Madame Morgane’s.

That is, if she doesn’t do a quick hook around to the house of the Accomplished Academics. Yes, she’ll go there. Their daughters are wonderful musicians, budding professionals whose violin and viola sweeten the air all summer. After that, it’s on to Celeste and Henry, the village psychiatrists. (Freudian.) Yes, Kerbordardoué is a full–service gossip stop for anyone, but especially empty–nest parents like Gwened. We’ve got everything you need right here.

*

As Gwened moves off, letter held high as a flag, I smile. If only my Anne had seen her like this, she wouldn’t have been so suspicious. “Tell me more about Gwened,” Anne had demanded early in her visit. “That’s her house above ours? She’s the one? The reason you’re here? You said she’s a professor. What else?”

“She’s a witch,” I said.

“No! Not really.”

“Mom believes she tried to seduce Dad with some kind of potion.”

“What? I can’t believe this! Mindy—-Donny’s making this up, isn’t he?”

“She was doing some kind of witch thing,” Mindy confirmed. “Right in front of your mother, she was casting a spell. And he really was falling for it.”

“I can’t believe it! This is so bizarre! How did she cast a spell?”

“Near the end of the trip, your dad cut his leg in the hotel swimming pool, and it got infected. Gwened noticed when we were having aperitifs. So she went over to her well and pulled out a handful of this slimy green moss and made a poultice out of it. Put it on his shin.”

“You’re telling a story. You’re both making this up. Donny? Is Mindy telling the truth?”

“All I can say is, it really did feel strange. I couldn’t believe it was happening myself. Gwened was chatting away in this very lulling voice, and Dad had this big smile on his face. He couldn’t take his eyes off her.”

“He couldn’t take his eyes off her boobs, you mean,” said Mindy. “She kept bending over right in front of him. She found a way to pop a button.”

“You mean he was falling for it? Dad? Nooooo! ”

“Women have their ways.” Mindy looked wise. “French women especially.”

“I think she scares me a little,” Anne said with a little shiver. “And I can’t wait for her to come to dinner tomorrow.” Laughter. “What will you guys cook?”

“Lotte, tomatoes, green beans, chorizo, zucchini, green salad, goat cheese.”

“Ooooh. Donny, where did you learn to cook?”

“I always cooked. In Boy Scouts, in college.”

“Not like this. I tasted your cooking in Santa Cruz. So where was it?”

“Here.”

“Who taught you? Gwened?”

“No…” Anne kept staring at me, so I shifted in my chair and started over. “I guess I started tasting food, really tasting, when Mindy first brought me to France. First tasting, then really paying attention to ingredients, then practicing in New York. One month in Belle Île, then the rest of the year trying to duplicate recipes, tastes. You can find anything in New York. Well, almost. I haven’t tasted a good American peach for years.”

“This is so amazing,” Anne said. “You know, it’s a whole world you have here. I want to spend more time here. Can I come next year?”

“You’d better!” Already, though, I had my doubts.

The boys are back, pulling up on their bikes to shout through the window: “No surf !”

“You’re sure?” I ask. “Who was in the water?”

“Nobody.”

“Will you be quiet, please?” calls Mindy from the dormer above.

“Sorry.”

“I’ve been going crazy listening to your mangled French all morning, discussing the most incredible banalities under my window.”

“Time to feed the Mommy,” I say to the boys, loud enough so Mindy can overhear it. To feed Mindy means dividing the omelet—-to Devo’s dismay—-then cutting bread and setting out little goat cheeses from my friend the cheese lady, who appreciates my French. Tomatoes and lettuce, oil and vinegar. At the foot of the staircase I call: “Lunch!” It’s only eleven o’clock, but food fuels good humor as well as activity.

And we must have activity.

The boys lay out their spear guns and masks and wet suits, talking of the fish they’ll hunt today when we finally head out. They eat, then resume the chess game. Time stops. I grab a book and sit out on the thin ledge of concrete that runs along the base of the foundation, toes in the grass. Bees buzz around. Swallows dip and nip midges. An hour passes. The king is trapped, the game resigned.

“Let’s go!” shouts Rory. We fill the bright Duty Free and striped Lancôme gift bags, now redolent of salty fish guts and sand, load a straw bag with towels, a thermos of hot tea, cookies, a Wiffle ball and bat, the Herald Tribune.

At the last second, Mindy joins us and insists we strap her surfboard on the roof rack. The old Renault turns over, smoking and shaking. As I work the choke in and out and feather the gas, the bright car of the movie starlet who lives at the top of the lane creeps out from between the hedges. She’s got her Garbo goggles on and a Japanese Red Army Faction head scarf, right out of a Godard film (which she hasn’t been in). Her blond daughter, Rory’s age, is nowhere to be seen, thank heavens. Or maybe that’s a bad thing—-we have to keep an eye on her. She grew up in Hollywood, and there’s a touch of Lindsay Lohan in her tempestuous nature.

Once the movie star is past, I can back up and point the car’s nose down the rutted lane. Staggering, blowing blue smoke, we scrape between Suzanne’s massed hydrangeas. The blossoms beating against the windows remind me of cheerleaders waving their pom–poms at football players as they emerge from the stadium tunnel.

Twenty feet later, the car stalls in front of Le Vicomte’s. “Rick” and Yvonne are sitting under an umbrella playing cards in cardigan sweaters and flannel trousers, while one bare–chested son, Thierry, smokes a cigarette and stuffs weeds into the flaming open hearth of a roofless sixteenth–century ruin. Everyone waves and offers salutations as I try to start the car.

Eventually we crawl up the road through the tunnel of trees. Madame Morgane scuttles away up her drive, her daughter–in–law going

the opposite direction to her own house. We exchange nods. At last we’re through the gauntlet and into open fields. But here comes an oncoming car. It’s Pierre–Louis and Sidonie, another psychiatrist couple—-Lacanians—-who live ten villages away from us. Stopping alongside, chatting through open windows, reaching out for a handshake, we make plans for an aperitif the following day and drive on. We’re getting there.

“God, it takes so much time to do anything here!” Mindy shifts irritably in her seat.

We take a left turn and run past the former surf shop, now reverted back to a cottage, the half–pipe gone where skateboarders used to practice roller coasters and rail grabs. We pass the house of the lawyer for the Big Important Newspaper, hidden by a dense palisade of tall straight Norfolk pines.

After a switchback series of turns into and out of dirt lanes and paved roads, passing the estate of the Majestic Madame Who Fought in the Resistance and Survived Auschwitz, we reach the stark “Village of Merde,” as we privately call this windswept cluster of houses, and slo–mo slalom around cats, ducks, chickens, a hog, several small children in Wellingtons splashing in lakes of animal shit, and finally a string of horses and Shetland ponies, all saddled up and ready to go. Poney Bleu à votre service, Monsieur et Madame! Stages, randonnées, promenades…

“Surf check,” Mindy says at the next crossroads. The boys complain, but they sound guilty. They probably blew it off this morning. Then again, boys always sound guilty.

Past some hunched–over whitewashed houses, once again in open fields, we carefully overtake cyclists and the occasional oblivious couple pushing a baby carriage in the middle of nowhere. And there’s Dede, pedaling his old clunker. The proprietor of the village, he is a large man in blue overalls and Wellingtons, huge head tucked into a newsboy’s cap, tin pail in his hand, going blackberrying on his lunch hour. “What’s for lunch?” asks Devo. Because it is, incredibly, lunchtime again.

The road dead–ends at the old ramparts of a fort, either Roman or Celtic, later repurposed by Napoleon and tweaked again by the Germans during the Occupation. Now it’s just a grassy ring by a graveled car park. At the cliff’s edge, we look down on Donnant, the most changeable beach in creation. After a minute Mindy decides she’s staying to see if the tide will bring a bump to the thin, glassy waves. She unstraps her yellow board and shoulders her backpack with towel, wet suit, second lunch. Down the cliff she goes on a narrow rock ledge, sure-footed on her wide–splayed toes—-luau feet, they’re called in Hawaii. Below on the glitter–green sea a couple of our surf crew float on their boards, talking.

With the mommy gone, the car goes tribal. Devo takes shotgun and slaps the venerable cassette into the car stereo. There’s only one song for going spearfishing: “Stand!” by Sly and the Family Stone. Heading down the corrugated dirt road with dust boiling in our wake, we sing at the top of our lungs while I pump the brakes in time.

Today’s dive spot is a rocky fjord with a beach of round stones. Ten feet out, a subterranean stream creates an underwater freshwater spring over a sand bottom. Thick kelp stalks swing in the slow pulse of swells. Once the boys signal that the water quality is good, I take off on foot up a narrow trail and follow the shattered cliff edge of the Côte Sauvage back toward Donnant. I bring my swim fins in case there is surf, but one look at Mindy and the crew floating on their boards is enough to keep me high and dry.

Walking back to the cove on a rabbit trail, I feel the sun drawing near and discharging great ripples of heat over the moor. Spongy mossy knobs under my feet sprout little red and blue and white flowers, and the gorse flares yellow. Even the thorns shimmer invitingly. When I reach the cliff overlooking the fjord, the boys are directly below, swimming slowly about a hundred yards from the rocky beach. They dive, cruise deep, surface with snorkels spouting.

Climbing down, I take up a place on a flat shelf of rock that isn’t too uncomfortable, lie back on my towel, and open my newspaper. Every few minutes a shout goes up, Rory and Devo devising tactics to drive their quarry into the open. I nap. When I open my eyes again, a fat, lime–green fish impaled on a spear is being thrust at me by a creature wearing a glass mask, with lips blue and teeth chattering. Fish and boy look remarkably alike.

*

So far the dive at the fjord has resulted in the single vieille, a soft–bodied rock cod of no great taste. I’ll need to supplement it with another fish, so a visit to Sauzon, our nearest town, is in order. I’ll have to fight the crowd at the quay when the boat comes in. The prospect makes me savor the Herald Tribune, squeezing every last drop of useless information out of its twenty–two pages. Financial tables, European soccer news, Italian politics—-as long as it is in English, I’ll read it.

Eventually the boys tire and strip off their wet suits and drape themselves over hot rocks. Then we load the car and shudder up the dirt road, over ruts like small canyons. I drive back to the old ramparts and we head down the cliff, only to find Mindy freezing and ready to leave. The thermos of tea and a slice of bread and cheese revive her. She decides to walk up the valley to the village to warm up and enjoy a quiet house. The boys join a loose gang in kicking a soccer ball over the long, wet sand flat left by the ebbing tide. A game starts.

The French lunch hour is over. People appear at the gap in the sand dunes where Les Sauveteurs en Mer have constructed a wooden stair. The families carry folding chairs, tents and sunshades, parasols and rubber boats. Babies cry; young people run, scattering sand. The tap–tap of endless paddleball games begins. Lifeguards stroll up and down in their bright emergency orange vests and Speedos, carrying waterproof walkie–talkies and swim fins clamped under one armpit. The elegance is itself reassuring.

It’s now or never for me, so I grab my fins and start down to the water, wishing Rory, Devo, and I could rethink our pact to never wear wet suits when bodysurfing. The water temperature is 61 degrees! Oh, the things we do to impress our kids and teach them the proper hardiness…

Of course, I want to impress the French, too. Show them we are true Americans, Californians, Hawaiians, endowed by our creator with a superhuman ocean sense and testicles that shrink to the size of raisins in the icy temps. Mustn’t let down the side. With a shudder, I push into the first ankle–high waves and begin the slow slog out to the impact zone a hundred yards offshore.

Forty–eight minutes later, I emerge to find half the village lounging on the hot sand. People leap to their feet to kiss my cheeks (and wince at how cold they are): Celeste and Henry, our village psychiatrists; Sidonie and Pierre–Louis, the psychiatrists from ten villages down; Yvonne, wife of Le Vicomte; and a handful of friends visiting from other villages or Paris. Gwened lies on her towel a discreet thirty yards away—-like Mindy, she prefers calm and quiet, less of a rhubarb, one of those quaint English words that has never lost the ability to provoke laughter in France.

The soccer game breaks up and the boys of several villages crash the circle of towels, plundering sacks of cookies: Le Petit Ecolier, Sablés Beurré Nantais, and the chocolate–and–orange–zest–covered marshmallow domes whose name we never tire of saying: “Goooters.” Girls scoot their towels closer, joining the circle. A couple of the older teens light up cigarettes, drawing eye rolls from the adults—-except for Sidonie, who turns to a fifteen–year–old.

“May I bum a smoke?” she asks in English, deadpan. Looks at me: “Bum is correct, Don? It eez not ze same as ass, no?”

I nod, but Celeste’s husband, Henry, wags a finger. “No, ze bum is ze ass, but only for ze Anglais. Yes, Don?”

“No, Henry,” I reply. “One must not forget that, pour les Anglais, ze ass is ze arse.”

Sidonie’s husband, Pierre–Louis, smacks his head. “Oh, but of course! Ze arse Anglais.”

The kids blush, trying not to look shocked but totally flustered. The cigarette pack goes back into a purse. Score one for the psychiatrists. Everyone cackles, trading double entendres, and an hour passes in beach blanket Babylon: French people trying to speak English, French teenagers practicing American rapper slang with the American boys, and the lone American adult addressing men as women and women as men and referring to himself as both—-a psychiatrist’s idea of heaven, for sure.

A football comes out and the boys began throwing and catching, moving ever closer to the sea. At their gestures, I heave myself up and join them—-activity, we must have more activity! Running brings the heat back into my limbs. Another hour passes.

Even at four o’clock the sun is bright, high overhead, but by French rules it’s getting late. People pack and drift back through the dunes to the parking lot. Just as I’m wondering what to do about dinner (I’ve missed the boat at Sauzon), Mindy comes across the sands carrying a straw basket filled with salami, apples, baguettes, beets in vinaigrette, and an oval fresh–baked cake.

“Hmm,” says Devo, eyeing the cake. “The chocolate football.” Another hour passes. With Mindy here, the conversation switches back to French, too fast and subtle for me to do more than nod and smile.

The crowd at the beach thins out. The twenty or thirty who remain scattered over a half mile of sand and rocky cul–de–sacs are revealed as a class: lovers and beachcombers and a few Bellilois come for an after–work plunge. We know quite a few. We are all thankful that, at this hour, discreet waves of the hand may be substituted for the usual getting up, going over, and kissing.

A loud air horn indicates Les Sauveteurs en Mer are going off duty. True lords of their domain, they receive salutations as they stroll up to their shed. Henry and Celeste and Sidonie and Pierre–Louis say they must go. We decline offers to join them for an aperitif and they don’t press the issue, knowing from long experience and surprisingly earnest debate that at certain tides, we simply will not leave the beach.

Our village rises as one, gathering towels and heading up through the dunes and into the grassy valley. As they go, they pass the next shift arriving: local surfers coming for the evening glass–off. Soloists scramble like goats down the cliff, boards snug under one arm and already in their wet suits. Others with families march up the sandy throat of the canyon loaded down like Bedouin caravans.

It is seven o’clock and I’ve been outdoors for five hours. Yet this is when the real action begins. The tide is coming up, and the little bump of this morning is now a swell with two distinct lines in the middle, a point break at each side caused by the rock islets that bookend the beach, and even a decent shore break where the kids with bodyboards go wild. The surfers are mostly Bellilois, with a few regular summer visitors. The lifeguards come down and join us, shedding their orange vests. Everybody in the water!

I join Rory and David and Celeste and Henry’s son, Marc, in the bare–chested bodysurfing brigade. We duck dive and kick under the onrushing white water. Eight minutes later, we’re on the outside looking in, floating on the heaving Atlantic with the cliffs and golden sand dunes glowing in the evening sun. An hour later and we’re still there, plus or minus a few friends who’ve come or gone, giving and taking waves.

The sun sinks slowly, yet I’d swear the water feels warmer. It’s because of the waves, of course—-our engine rooms are stoked by the constant kicking, diving, stroking, and best of all, the adrenaline rush of sliding down the steep faces. Sluicing along in the concave half–pipe of green sea. Making section after section, passing your friends paddling out, hearing them hoot.

I gather myself at the peak of a large swell. As it starts to topple forward, I slice down on my chest and angle for the heart of the tube. Inside, for a moment, all is quiet and hissing, then the walls implode. The breaking wave takes me into an underwater world that alternates from light to darkness, rolling me and spinning me. My heels strike the sand bottom a good ten feet deep as the wave plunges silently past, like a waterfall. A hard hold–down, followed by a twitchy release from the ocean’s coils that says: Okay, I’m done with you, for now. Just don’t try that again.

Far inshore, on the beach in the advancing shadows, I can just make out specks of people walking the beach. The after–dinner contingent has arrived. And still we linger.

/

Don Wallace has written fiction and non-fiction, journalism, films, reviews and opinion pieces, even the odd poem and song. He writes about a number of diverse environments: France, surfing, military history, business and entrepreneurs, the boating world, bass fishing, high school football, civil rights and Hawaiian music.

Don Wallace has written fiction and non-fiction, journalism, films, reviews and opinion pieces, even the odd poem and song. He writes about a number of diverse environments: France, surfing, military history, business and entrepreneurs, the boating world, bass fishing, high school football, civil rights and Hawaiian music.

He has been a magazine editor at Time Inc., Hearst, the New York Times, and Conde Nast and was most recently Film Editor at The Honolulu Weekly. From Long Beach, California, he attended Long Beach Poly, UC Santa Cruz, and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop; with his wife Mindy Pennybacker he lived in New York City for 27 years before returning to Mindy’s native Honolulu in 2009.